Will New Zealand’s ‘patronising’ aid freeze push Cook Islands closer to China?

The funding cut leaves the Cook Islands facing a sudden financial shortfall, prompting warnings that Wellington’s approach could backfire

What began as a quiet series of infrastructure deals between the Cook Islands and China has erupted into a diplomatic stand-off, with New Zealand halting millions in aid and Pacific leaders accusing Wellington of “patronising” behaviour.

New Zealand’s abrupt suspension of aid has cast a harsh spotlight on the country’s growing unease over China’s expanding Pacific footprint, drawing warnings from regional observers that the move risks appearing “coercive rather than constructive”.

Wellington announced on June 19 that it was freezing millions of dollars in funding to the Cook Islands, citing a lack of transparency surrounding a suite of deals struck between the archipelago and China.

“We’ve suspended some of the aid money until we can get clarity on those issues,” Prime Minister Christopher Luxon said from Shanghai during his first official visit to China.

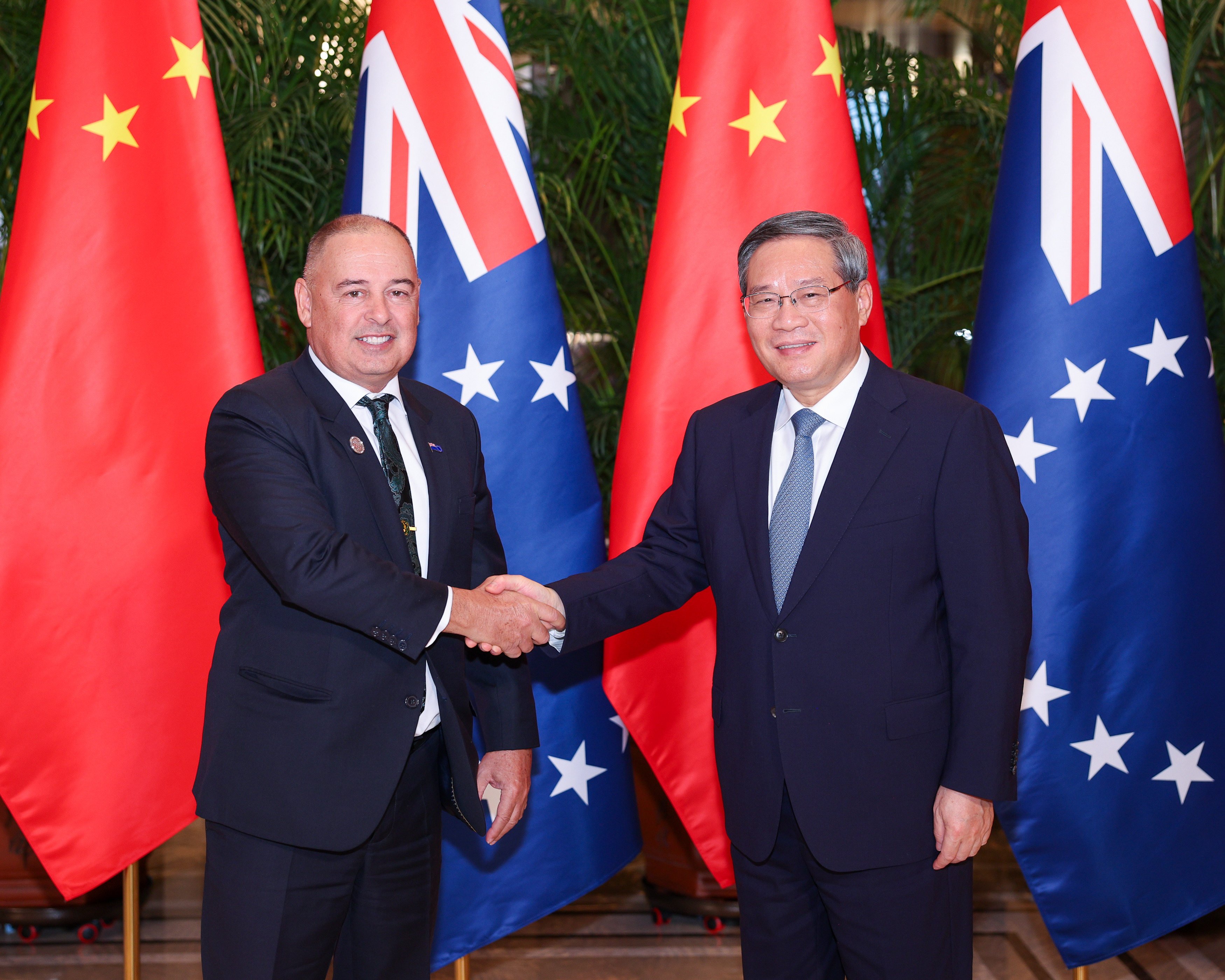

Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown hit back the next day by accusing Wellington of being “patronising”, contending that the relationship should be “defined by partnership, not paternalism”.

In parliament, Brown defended his government’s engagement with Beijing, insisting that these ties did not “compromise” the islands’ independence and stressing that no military or defence arrangements had been made.

The Cook Islands is self-governing but has a “free association” relationship with New Zealand, its former colonial ruler. Wellington is its primary financial backer, providing budgetary assistance as well as help on foreign affairs and defence, and the two share the same passport.

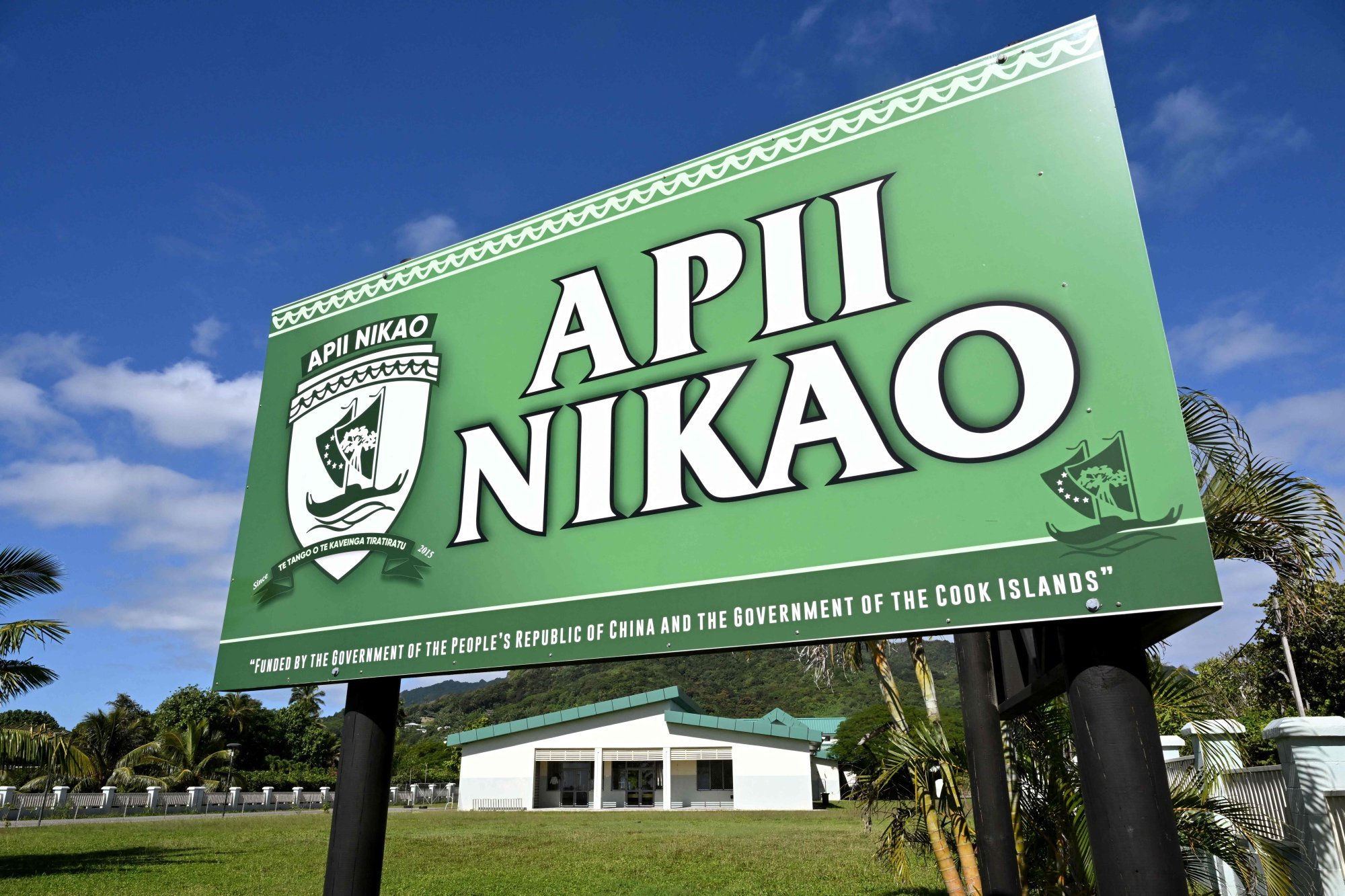

The agreements signed by Brown during a visit to China in February included pledges for infrastructure investment and educational scholarships from Beijing. Some of these deals were not initially made public, however, heightening suspicions in Wellington.

Former Australian diplomat Solstice Middleby told This Week in Asia that the timing of Luxon’s announcement “is more than coincidental”.

“New Zealand’s decision to suspend aid while the prime minister is in China appears designed to send a message to both domestic and international audiences about its discomfort with deepening China-Pacific ties,” said the PhD candidate in Pacific regionalism at the University of Adelaide.

Its aid freeze risks being seen as coercive rather than constructiveSolstice Middleby, former diplomat, on New Zealand

“Unless [Wellington] articulates concrete concerns, such as transparency, debt sustainability, or dual-use infrastructure, its aid freeze risks being seen as coercive rather than constructive.”

Middleby argued that the suspension seemed less a matter of principle than “punishing” a sovereign decision by the Cook Islands that diverged from Wellington’s preferences.

The move, she warned, risked reinforcing a geopolitical narrative that casts Pacific island nations as mere pawns in a contest for influence, rather than sovereign actors pursuing their own development goals.

Pacific nations have emerged as something of a diplomatic battleground in recent years, coveted for their location astride vital sea lanes and their potential for military basing. Competition between China and the United States and its allies – including Australia and New Zealand – has intensified, particularly since 2022, when the Solomon Islands’ security pact with Beijing triggered Western alarm over a possible Chinese military presence in the region.

Both sides have since redoubled efforts to woo Pacific nations through aid, trade and diplomacy.

But the fallout from Wellington’s aid freeze is already reverberating through the Cook Islands, where the government now faces a sudden shortfall.

A report presented this month by the Cook Islands’ Public Accounts Committee flagged a NZ$10 million (US$6 million) reduction in government coffers – the first public confirmation of the freeze’s financial impact. The funds, earmarked for “core sector support”, underpin health, education and tourism with close auditing by Wellington. Over the past three years, New Zealand has channelled NZ$200 million to the islands.

Middleby warned that the funding freeze had strained the relationship of trust and mutual respect that underpinned the free association arrangement.

“If New Zealand continues to use aid as leverage, it may unintentionally accelerate the very diversification of partnerships it seeks to prevent,” she added.

The Cook Islands’ “free association” with New Zealand dates back to 1965, with a subsequent Joint Centenary Declaration signed in 2001 obliging regular consultation on defence and security matters. Observers say Wellington believes it should have been privy to the details of the China agreements before they were signed – a sentiment echoed in New Zealand media coverage.

Alan Tidwell, director of Georgetown University’s Centre for Australian, New Zealand and Pacific Studies, said Wellington clearly thought the Cook Islands had “overstepped the mark” and failed to consult it adequately.

“Whether a short-term measure or a longer-term punishment, Wellington’s aid cut will have consequences,” Tidwell said. He added that New Zealand’s move appeared calculated to pressure the islands’ government and potentially motivate domestic opposition.

While the Cook Islands could, in theory, assert full independence – adopting its own passport and currency – Tidwell said that it had already “blocked this avenue” by previously rejecting the creation of its own passport.

“The cut in aid is one more pressure point on the Cook Islands to work with Wellington and better manage their bilateral affairs,” Tidwell said.

New Zealand, he added, wanted to “reset” the 2001 agreement by “codifying consultation to avoid ever again having this trouble”.

“As I understand it there will be no more high-level meetings until this takes place,” Tidwell said.

After efforts to reassure Wellington failed, the Cook Islands dropped a proposal to introduce its own passports in February.

For its part, Beijing insists its outreach is benign. “China-Cook Islands cooperation targets no third party, nor should it be interfered with or constrained by any third party,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Guo Jiakun said in February, adding that the deals were intended solely to benefit the Cook Islands’ 15,000 people.

Middleby, meanwhile, said the aid freeze had exposed a deeper tension at the heart of New Zealand’s Pacific diplomacy.

“[There is] a clash between its self-image as a benevolent partner and its discomfort with Pacific nations exercising independent foreign policy choices,” she said, adding that the move had further alienated smaller Pacific nations from their traditional partners.

Additional reporting by Associated Press