A drop in the ocean? Pacific nations tap local know-how for marine conservation

Among the measures being taken are a ban on fishing and mining activities in vast marine protected areas

Pacific island nations are racing to enhance marine conservation, establishing sweeping “no-take” zones and pledging to sustainably manage vast swathes of their territorial waters despite facing limited resources and geopolitical pressure.

Among them, Samoa last month unveiled a ban on fishing, mining and other extractive activities over 30 per cent of its ocean territory by 2027. The move will create 36,000 sq km (13,900 square miles) of marine protected areas (MPAs) – more than 12 times the country’s land size.

“Like other Pacific island nations, challenges like marine habitat destruction, overfishing, and pollution threaten the health of Samoa’s ocean, which endanger the well-being of our people,” Toeolesulusulu Cedric Pose Salesa Schuster, Samoa’s natural resources and environment minister, told This Week in Asia.

“Samoa’s marine spatial plan addresses these urgent issues and offers solutions to sustain the ocean and what it provides for us now and for future generations.”

Such planning has become increasingly common across the Pacific, even as global progress on the so-called “30×30” pledge – to protect 30 per cent of Earth’s land and ocean area by 2030 – has slowed.

French Polynesia has committed to fully protect more than 1 million sq km (390,000 square miles) of its waters. Tonga, Niue and New Caledonia have already enacted expansive MPAs. At the UN Ocean Conference (UNOC) in Nice held earlier this month, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu announced plans for a Melanesian Ocean Reserve that – once formalised – would safeguard over 6 million sq km of ocean by tapping indigenous knowledge.

Together, Pacific island nations control over an ocean area roughly the size of Africa. While they contribute relatively little to global emissions, they are on the front lines of climate change – increasingly vulnerable to extreme weather, rising sea levels and the economic fallout of environmental degradation.

“The nations of the southwest Pacific have produced a stunning example of the potential for multi-country agreements to accelerate meaningful ocean protections,” said Barbara Quimby, an assistant professor of marine science and policy at Hawaii Pacific University.

Quimby credited the region with pioneering a hybrid approach integrating traditional values and village-based governance with scientific data and national policy. “For decades, efforts in Samoa, Solomon Islands, Fiji and other locations have demonstrated the power of hybridised management,” she said.

Samoa’s new plan includes a 24-nautical mile (45km) zone reserved for traditional Alia tuna fishing vessels to reduce competition from industrial fleets and is part of a broader commitment to sustainably manage its 120,000 sq km (46,300 square-mile) ocean territory.

But marine conservation experts have warned that the implementation of such measures in the Pacific remains a formidable challenge.

Only 8 per cent of the global ocean is designated as an MPA and less than 3 per cent is classified as fully or highly protected, according to an assessment by Dynamic Planet and National Geographic’s Pristine Seas project in May. The latter is widely considered the minimum level needed for marine life to effectively recover the damage caused by overfishing, pollution, habitat destruction, and global warming.

“So far we haven’t been very successful in using the ocean in a way that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs,” said Enric Sala, a co-author of the study and founder of National Geographic’s Pristine Seas project.

The only notable exception was the no-take MPAs, where marine life could restore itself to levels that were on average five times greater than in nearby unprotected areas, he added.

But the commitment towards creating MPAs has been uneven across regions.

“Most of the new MPA designations and firm commitments to create more MPAs came from Pacific nations. Very little came from the rest of the world in comparison,” Sala said of this month’s UNOC, calling on countries that backed 30×30 to implement their plans.

To meet the 2030 goal, roughly 1,000 sq km (386 square miles) of marine areas would need to be protected every day, according to the study by Dynamic Planet and Pristine Seas. This is an undertaking that requires money and manpower, according to Fanny Douvere of Unesco’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission.

Financial resources required for MPAs are in short supply for many Pacific island nations, where small populations are spread across widely dispersed islands. Insufficient data, uncertainty and capacity constraints severely limit the region’s capacity to plan for and react to climate risks, threatening its long-term development efforts, the Asian Development Bank has warned in a report.

The importance of initiatives such as the creation of MPAs to bolster the economic well-being of these nations amid climate change cannot be underestimated. A World Bank report released earlier this month shows that growth in the region might have fallen to 2.6 per cent in 2024 due to climate-related shocks and global economic uncertainty.

Marine monitoring remained labour-intensive and costly and without proper enforcement, “MPAs are just lines on a map”, Douvere said.

Many Pacific island nations have begun using drones and satellites to monitor illegal fishing, and some are also exploring the use of artificial intelligence, Quimby said. But sustainable management requires sustained human investment and international cooperation, especially across migratory corridors and overlapping exclusive economic zones, according to Douvere.

“As exemplified by the US’ recent reversal on fishing protections for the Pacific Islands National Marine Monument, all state-based MPAs are dependent on the will and policies of the governing nation,” Quimby said, referring to US President Donald Trump’s decision in April to reopen the vast marine reserve, located southwest of Hawaii, to commercial fishing.

Sustainable MPAs must take into account local interests and the relationships between fishers, officials, and community leaders, Quimby added.

The urgency is mounting for Pacific countries to carry out their marine conservation plans as global warming accelerates.

According to the World Meteorological Organization, 2024 was the hottest year on record in the southwest Pacific. Rising sea temperatures, acidification and coastal run-off are damaging coral reefs and threatening the region’s food security.

Many Pacific economies depend heavily on fishing and tourism – sectors that are climate-sensitive and resource-intensive. Such reliance on ocean-based industries, while central to these nations’ development, makes them acutely vulnerable to marine ecosystem collapse, the International Monetary Fund has warned.

Global funding for marine protection remains another obstacle as only US$1.2 billion has been invested annually, far short of the US$15.8 billion required each year to meet 30×30, according to a report by a group of nature NGOs and funders, including the Bloomberg Ocean Fund and WWF International, released in June.

“That’s less than the over US$20 billion that governments spend every year on harmful fisheries subsidies – that is, subsidising overfishing,” Sala said. “The money is there, only that governments decide to use it for depletion instead of regeneration.”

Strategic competition among more powerful nations looking to expand their foothold in the Pacific could complicate marine conservation plans.

As of 2022, Australia remained the region’s largest provider of official development assistance, accounting for around 40 per cent of total aid, worth US$1.5 billion, while China and the US were the second- and third-largest donors at US$256 million and US$249 million, respectively, according to a report by the Lowy Institute.

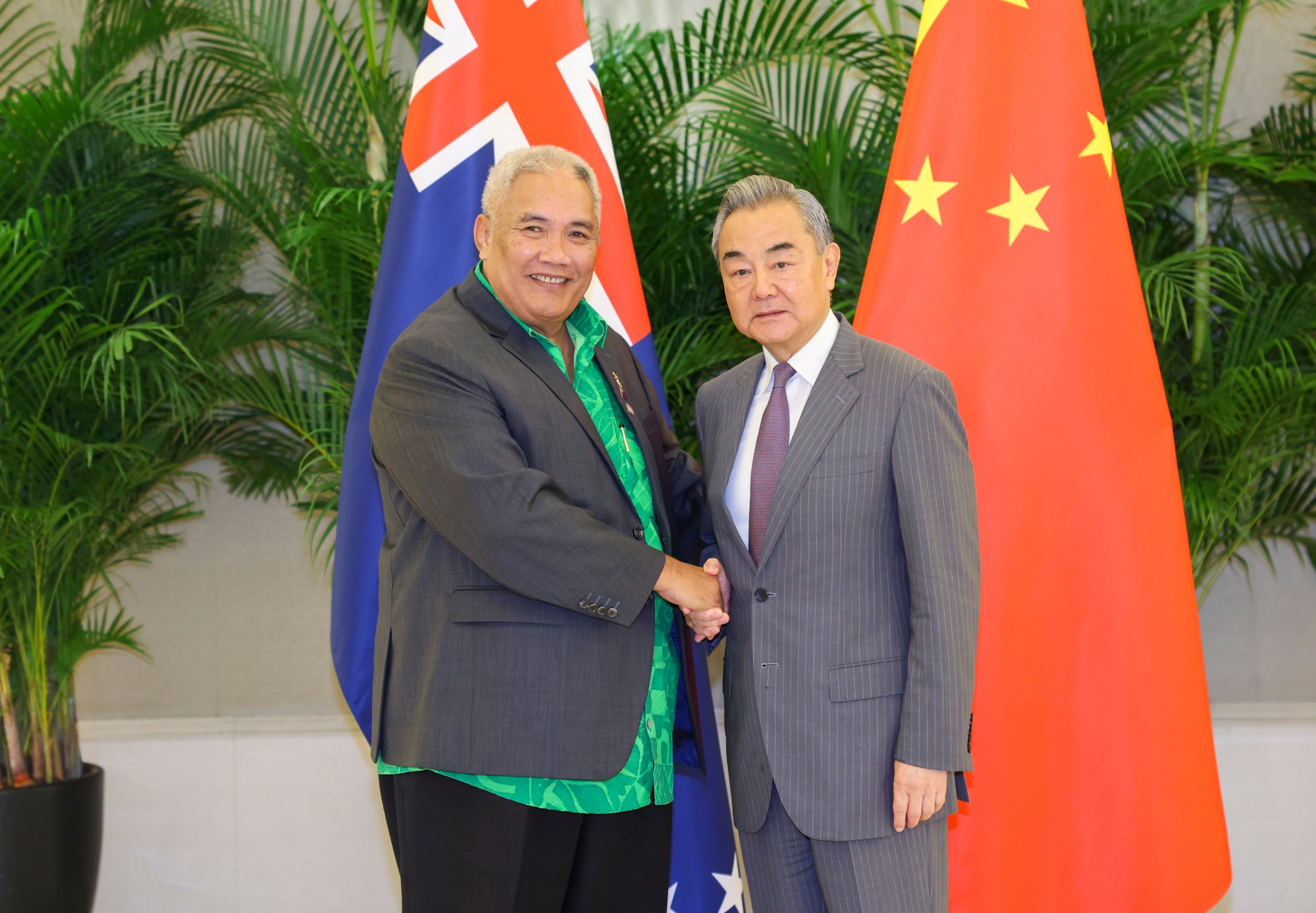

Tensions have risen in the Oceania region recently due to steps taken by some Pacific island nations, such as the Cook Islands, to deepen ties with China.

In February, Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown signed a US$4 million partnership agreement with China covering seabed mining and infrastructure. New Zealand responded last week by suspending NZ$18.2 million (US$11 million) in core development funding for the Cook Islands, citing a breach of trust and lack of transparency.

The Cook Islands is in ‘free association’ with its former colonial ruler New Zealand and has the autonomy to establish diplomatic relationships with other countries. In 2001, New Zealand and the Cook Islands signed a joint declaration requiring both sides to “consult regularly on defence and security issues”.

New Zealand was the Cook Islands’ biggest financial backer from 2008 to 2022, according to a report by the Lowy Institute.

Last month, China hosted leaders and officials from 11 Pacific island nations at a summit in which it pledged a US$2 million climate fund to support 100 “small but beautiful” environmental projects.