Why India and Pakistan are courting Afghanistan’s Taliban rulers

Need for a united front, business opportunities and China’s growing footprint among factors for changing calculus in South Asia, analysts say

The Taliban may be the unexpected beneficiaries of India and Pakistan’s recent conflict, as both countries court Afghanistan’s hardline government, which is yet to be formally recognised by any nation since seizing power four years ago.

Several days after launching air strikes against Pakistan for its alleged involvement in a militant attack which killed 26 civilians in Indian-administered Kashmir, India’s Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar spoke to his Taliban counterpart – Amir Khan Muttaqi – to thank him for condemning the attack.

In his first-ever discussion with Afghanistan’s Islamic government since their 2021 comeback, Jaishankar reiterated India’s continued support for Afghanistan’s development needs.

India has been cautiously re-engaging with Kabul over the past two years, sending food, medicines and vaccines – welcomed by the isolated Taliban, which has had few friends to call on since its stunning return to power after nearly two decades of war.

In January, Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri held talks with Muttaqi in Dubai over trade and regional security, a diplomatic outreach seen as recognition by New Delhi of the changing geopolitical realities of South Asia.

Initially, the return of the Taliban was a diplomatic blow to Delhi as Indian officials feared that the country would once more become a haven for militants from Pakistan.

But the calculus appears to have changed.

“Afghanistan is crucial to India to establish a common front against Pakistan as well as for business opportunities including its cache of mineral deposits,” said Uday Chandra, assistant professor at Georgetown University.

On the other hand, Islamabad has sought to staunch the flow of Afghan refugees across the Durand line – a colonial-era boundary dividing Afghanistan from Pakistan that has never been formally recognised by any Afghan state.

“Each side sees the other as trying to outflank it vis-a-vis a key neighbour. Rebalancing diplomatic ties [with] Afghanistan seems important for both India and Pakistan as a result,” Chandra said.

Bad neighbours

Relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan have deteriorated over the past few months as Islamabad evicts tens of thousands of Afghan refugees over security concerns, saying that armed groups launched attacks inside Pakistan from across their border – allegations Kabul denies.

“The earlier assumption was that the Taliban government will have strong ties with Pakistan, but we [India] soon realised that there are differences between the Taliban and Pakistan,” said Ajay Darshan Behera, professor at the Academy of International Studies at Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia University. “And that the Taliban is not behaving like a pawn of Pakistan.”

But last month Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar said relations between the two nations had improved since an April visit to Kabul.

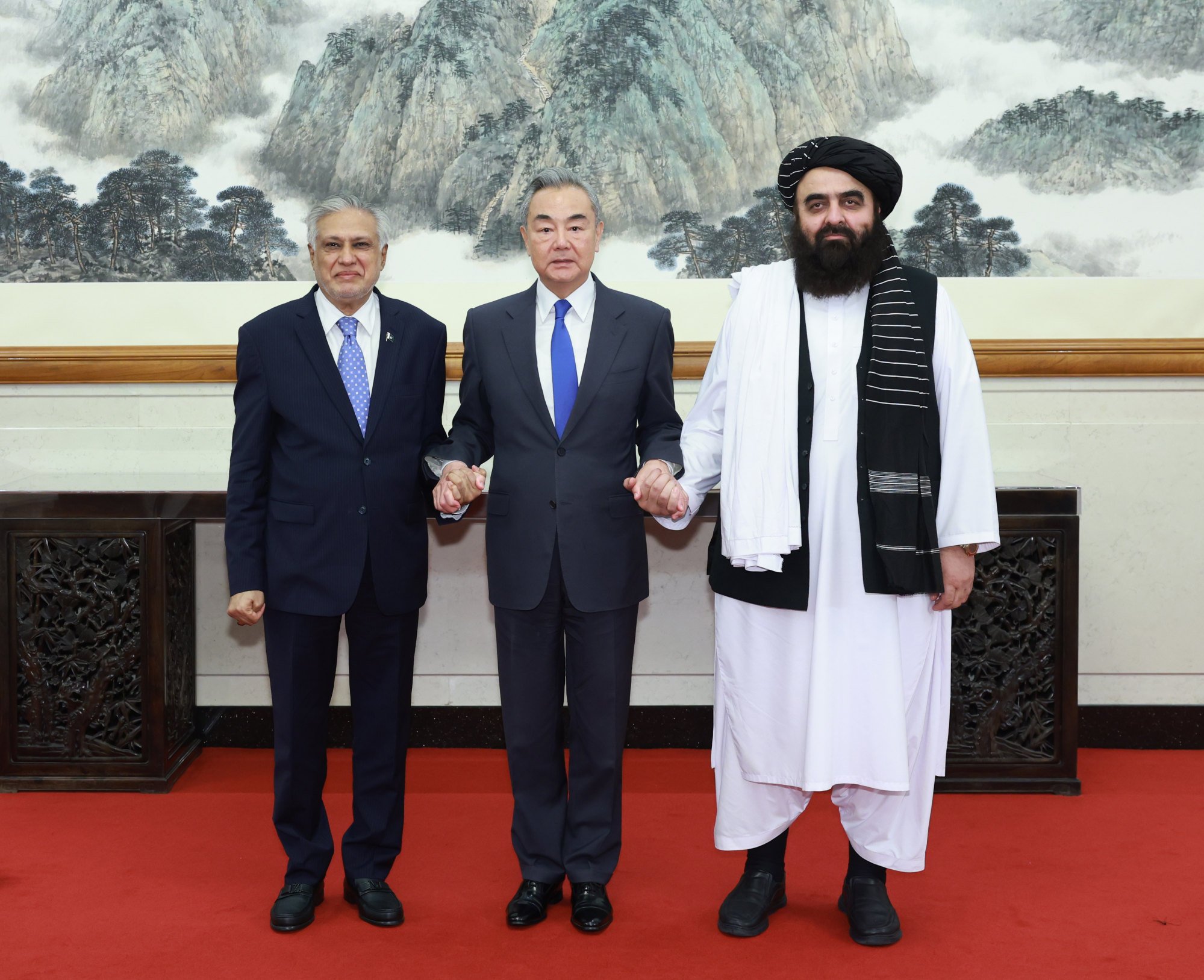

He also met Muttaqi and their Chinese counterpart Wang Yi during a trilateral meeting in Beijing last month.

Islamabad’s recent engagements are partly because Afghanistan’s Taliban regime in some ways was seen to have sided with India in the recent India-Pakistan conflict.

“That is a cause of worry for Pakistan,” Behera said. “It cannot have hostile forces all around.”

Port potential

The evacuation of US troops from Afghanistan in 2021 also left a vacuum for influence. China stepped into the gap and pressed its interests, including the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – connecting China’s Xinjiang province to Pakistan’s Gwadar Port that will be key to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Cordial ties between Afghanistan and Pakistan are key to that project.

But Beijing’s engagement with both countries to extend the CPEC to Afghanistan poses a big worry for Delhi.

“India now seems worried about allowing China to have that kind of footprint in Afghanistan,” Behera said.

Afghanistan’s appeal also lies under its soil. The country is believed to possess vast and untapped mineral resources, with estimates suggesting deposits worth trillions of dollars.

These resources include iron ore, copper, aluminium and rare earth elements, as well as precious and semi-precious gems and minerals like lapis lazuli.

It is also pivotal to India’s deep-water Chabahar Port project in Iran, which is strategically located on the Gulf of Oman and offers India a vital route to Central Asia bypassing Pakistan. India signed a fresh 10-year deal in 2024 to keep developing the port, despite US pressure to isolate Iran over its nuclear ambitions.

US President Donald Trump indicated progress in talks last month, saying that Iran had “sort of” agreed to the terms of a nuclear deal with the United States to scrap its uranium enrichment programme to prevent the country from developing nuclear weapons. Iran has denied any such programme and says its nuclear activities are entirely peaceful.

However, the prospect of a deal has again been thrown into uncertainty, with Israel launching strikes on Friday targeting the heart of Iran’s nuclear programme. The US has said it was not involved in the strikes, which also hit Iran’s main nuclear enrichment facility.

If the US and Iran still go ahead and strike a deal over Teheran’s nuclear programme, then the Chabahar Port project could be back on the table for India, according to Vivek Mishra, deputy director of the strategic studies programme at the Observer Research Foundation.

Blocked from land access to Iran by Pakistan, Afghanistan’s land corridor will become increasingly crucial to India as the Chabahar Port grows. And for that, Delhi needs friends in Kabul, driving the increasingly pragmatic embrace of the Taliban.

In return, the Taliban appear – at least for now – to be saying all the right things, according to Mishra.

The regime “has not made any anti-India statements and given out statements against terrorism”, he added.