China as a global conflict mediator: from ambition to action

From Saudi-Iran rapprochement to Myanmar ceasefires, China’s conflict diplomacy also aims to protect its own interests

China has increasingly taken on the role of conflict mediator on the world stage – hosting negotiations, proposing peace plans and even deploying personnel to oversee ceasefires. Once reluctant to engage in United Nations peacekeeping activities, it now provides more troops than any other permanent member of the Security Council.

These are dramatic shifts for a country that was once a staunch advocate of non-interference. As its economic and security interests now reach far beyond its borders, China’s engagement on the world stage has understandably grown accordingly. It has a strong incentive to resolve conflicts that threaten its trade, overseas investments, citizens abroad or simply regional stability.

The six-party talks on the North Korean nuclear issue, beginning in 2003, marked China’s first major foray into multilateral conflict mediation.

The talks provide a good example of China’s approach to conflict mediation, summarised in its foreign policy lexicon by the phrase “劝和促谈” (persuading for peace and promoting dialogue): while Beijing had no coercive leverage over Pyongyang, it served as a consistent convenor – urging North Korea to halt its nuclear ambitions while pressing the US to address the country’s security concerns.

China’s ambitions are now broader. It has been positioning itself as a leader of the Global South, embracing inclusive multilateralism more than the West.

The Global Security Initiative, launched in 2022, rich in principles but deliberately ambiguous in substance, signals Beijing’s growing appetite to reshape security diplomacy around its proposed set of global norms, which prioritise non-interference, dialogue and cooperation.

As conflicts drag on from Ukraine to Gaza, the global demand for effective mediation has never been higher. At the same time, the US under President Donald Trump is retreating from sustained engagement, giving China the space to step in. However, as mediation requires time, resources and political capital, the questions are where, how and to what effect China chooses to engage.

Where to resolve conflict

Rather than espousing universalist approaches to peace, China has been engaging most where it sees potential benefits – for itself and for others – that merit the resources and effort required. The cases of Saudi-Iran, Myanmar and Russia-Ukraine provide illustrations.

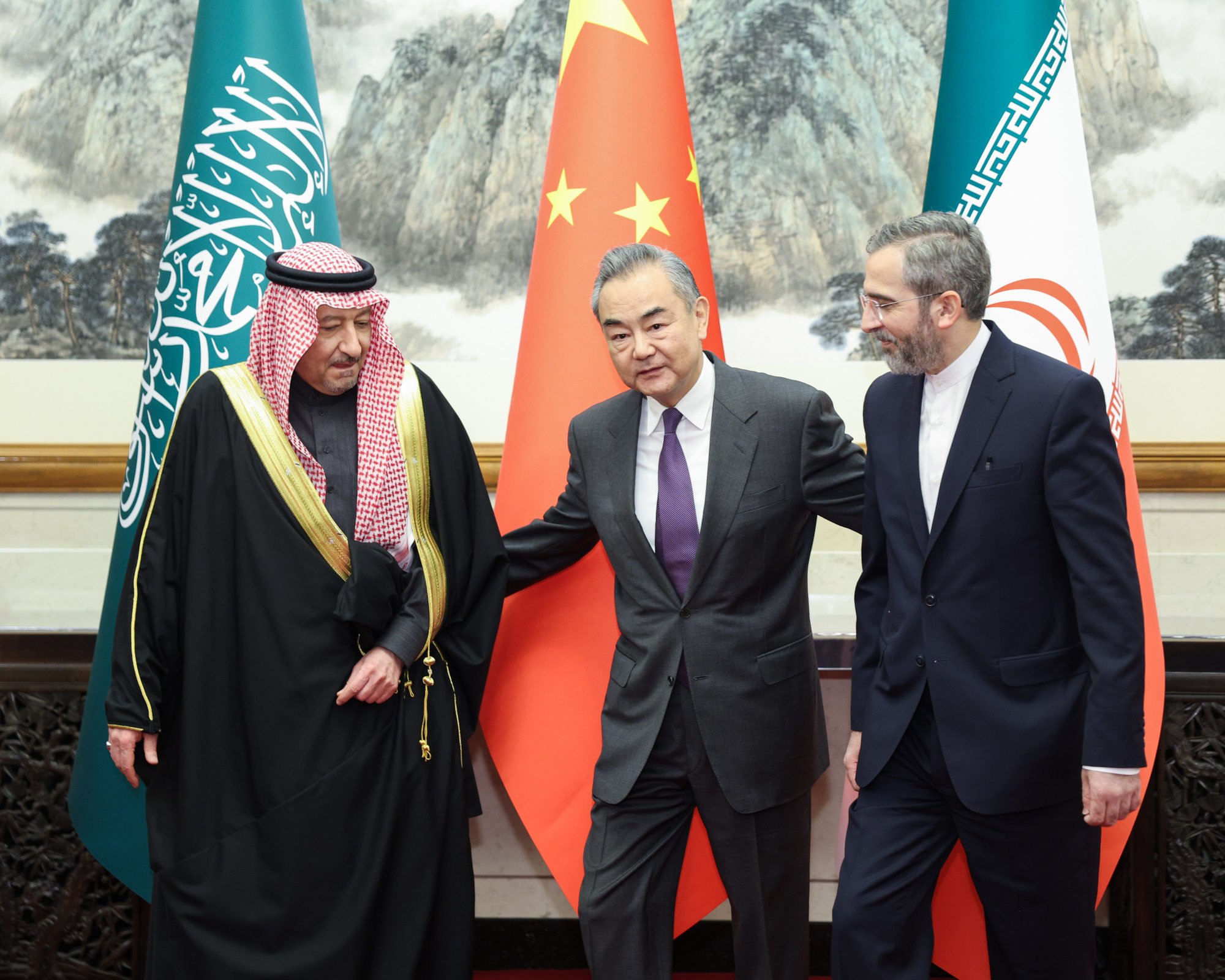

The Saudi-Iran agreement reached in 2023 was hailed as a diplomatic success and a shift from China’s traditional non-involvement. Yet, while China did facilitate engagement behind the scenes, both sides were already on a path to improved relations. The agreement represented a tactical rapprochement rather than a fundamental reconciliation. It did not require China to resolve deep-rooted conflicts or manage volatile post-agreement transitions. China scored a diplomatic win that advanced relations in the Middle East and gained kudos for its contribution with limited risk and effort.

By contrast, Myanmar highlights the deeper drivers – and limits – of China’s mediation ambitions. Earlier this year, it brokered a ceasefire between the military junta and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army – and, in a striking departure from its long-standing policy of non-interference, dispatched a monitoring team to supervise enforcement. This shift from quiet facilitation to active oversight underscores how China’s mediation is rooted in its economic and security imperatives. Stability in Shan state matters not only for border security but for safeguarding China’s access to rare earth minerals critical to its hi-tech industries.

Finally, given the Ukraine war’s significance for Europe, the US and Russia, it is difficult for China to avoid taking a stance on how the conflict should be resolved. Yet the differences between Russia and Ukraine are stark, perhaps irreconcilable. China has therefore limited itself to outlining rather ambiguous proposals instead of making a full-fledged effort at mediation. In 2023, it issued joint peace proposals with Brazil, emphasising dialogue without preconditions and mutual security guarantees, diverging from the West’s rights- and sovereignty-based frameworks. Special Envoy Li Hui’s shuttle diplomacy in Brazil, Egypt and Indonesia aligned China with the Global South’s call for alternative, stability-focused approaches to conflict resolution. Some Western analysts have questioned China’s willingness to act as a truly impartial broker that engages Russia and Ukraine on equal terms, considering Beijing’s close ties to Moscow.

How to resolve conflict

China argues that it adopts a different approach to conflict resolution than the West; that it emphasises facilitation over prescription, flexible processes over rigid frameworks, and economic incentives over normative demands. China stresses the need to avoid what it sees as the risk of hegemonic overreach and argues that it deliberately avoids imposing its will, preferring to facilitate dialogue instead of applying pressure or imposing norms tied to democracy, human rights, or governance reform.

This approach draws on Confucian philosophy, which emphasises “和谐” (harmony) over confrontation and sees conflict as a rupture in relationships rather than a clash of rights or ideologies. This outlook is amplified by the concept of “关系” (relationship), which prioritises trust and mutual benefit over public adjudication or moralising. Consistent with this world view, China’s diplomacy emphasises the quiet management of tensions and the need to preserve face for all parties rather than assigning blame.

Indeed, prominent Western mediators also emphasise trust, common interests, patience and symbolic gestures – principles not so different from a Confucian-informed ethos. Moreover, attractive as a Chinese alternative may appear, especially to the Global South, China’s “non-intrusive” style may be less a deliberate philosophy and more a reflection of its limited experience in conflict resolution.

Showing impact

China’s coming of age as a conflict mediator is both inevitable and consequential: its willingness to engage in conflict diplomacy offers new possibilities as its global footprint grows and traditional Western leadership evolves. Wherever and however China engages in conflict resolution, what matters is the practical impact: fighting stopped, lives saved, people safe and back to living normal lives.

However, unlike the US or European Union, which have spent decades working on complex peace processes, China is relatively new to the arena. It has yet to show whether it can manage the intricate work of post-conflict institution-building, transitional justice, or ensuring implementation of fragile agreements. Performative efforts issuing peace plans that lead nowhere will bring, at best, transitory benefits for China and soon lead to greater cynicism about any engagement by China.

China’s ability to be a truly effective mediator rests ultimately on three foundations. First, its ability to build trust with all parties involved. Indeed, the presence of such trusted relationships helps identify those conflict situations where China is best placed to play a constructive role. Second, its willingness to acknowledge where its interests are aligned with those in conflict and where they are not. This is not a uniquely Chinese challenge. All mediators, including the US, pursue their interests to some degree; what matters is transparency, balance and credibility. Finally, success requires the willingness to persist and put in the effort required to secure lasting agreement: as Chinese President Xi Jinping might put it, the need to “struggle” to end conflict. In a multipolar world starved of effective diplomacy, the opportunity for China is real. Success will demand not just ambition, but patience, impartiality and a willingness to struggle for peace, even when it tests China’s interests. Turning ambition into action is now China’s diplomatic test.

Andrew Cainey is Director and Co-Founder of the UK National Committee on China and Senior Associate Fellow, Royal United Services Institute. Xie Chengkai is Schwarzman Scholar at Tsinghua University. This article was first published by the Asian Peace Programme (APP), an initiative to promote peace in Asia, housed in the NUS Asia Research Institute.