With 50 years of history, Manila and Beijing should do better diplomacy

Stop allowing South China Sea spat to poison the waters when there are in fact many areas of potential cooperation for mutual benefit

June 9 marks the 50th anniversary of Philippines-China relations, ties steeped in history but marred by friction in recent years. Sadly, an overemphasis on the intractable sea dispute has polluted broader connections, stunting economic cooperation and stigmatising people-to-people exchanges. This is irrational and unproductive.

For Manila to make the sea row front and centre of ties is a tragedy of its foreign policy. For China to see its smaller neighbour as a mere pawn in its great power competition with Washington is a recipe for misunderstanding; it lets down Beijing’s neighbourhood diplomacy.

Allowing security issues to dominate relations is neither wise nor strategic. Confining ties to maritime tensions, alleged spying and influence operations limits their scope and potential. Describing your big neighbour as an adversary can be a dangerous, self-fulfilling prophecy. Increasing pressure on a smaller neighbour may push it deeper into a rival’s embrace.

Other Southeast Asian coastal states with similar concerns assign less publicity to their sea rows and employ more effective strategies. Manila and Beijing should do better diplomacy.

First, there are many areas where the two can work together without compromising their positions. China is the world’s greatest economic miracle, lifting 800 million people out of poverty in four decades. It is the world’s largest consumer and tourism market, a rising investor, the biggest producer of renewable energy and electric vehicles, and a leading player in mineral processing.

The Fortune Global 500 list last year had 133 Chinese companies, including three in the top 10. The State Grid Corporation of China, which has a 40 per cent stake in the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines, is ranked third. Five of the top 10 Asian universities ranked by Times Higher Education are from mainland China. The South China Sea dispute should not crowd out partnerships in areas where China has made great strides.

Agriculture, infrastructure, green energy and mobility, higher education, poverty reduction, tourism and climate action are areas of confluence – but these may not get traction if both sides are fixated on their sea spat.

Second, the South China Sea has a longer history of connecting than dividing. Despite linking both peoples for centuries, no part of the Philippine archipelago was subjugated by China, even at the height of its maritime might in the early 15th century.

Indeed, when a Sulu sultan who had been visiting the Ming emperor died on his way home in Dezhou, Shandong, he was buried with full honours – his royal mausoleum still sits there. From the late 16th to early 19th century, Manila served as a gateway for Chinese goods to reach Europe.

Chinese influence manifests in Filipino cuisine, customs and vocabulary. Intermarriages created lasting bonds, and Chinese migrants made indelible contributions to Philippine history, culture, economy, politics and civil society. Audacious voyages across the sea helped to build these enduring connections. The sea has long been an economic and cultural passageway, rather than a security hotspot.

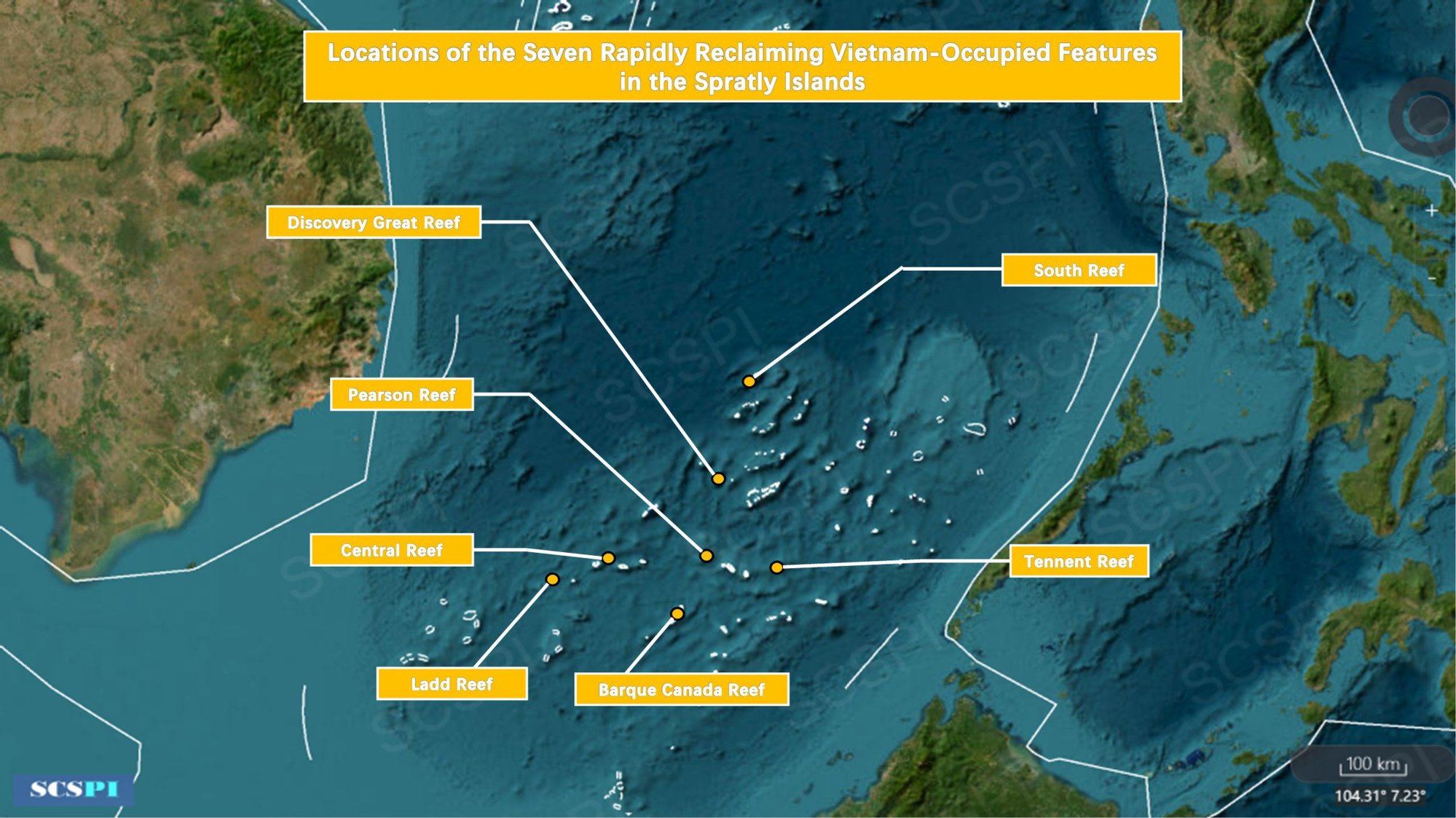

Third, tensions aside, other claimants still get what they want without needlessly antagonising China. Vietnam occupies the most features in the Spratlys and has been busy building structures in the contested reef chain without seemingly any physical interference from China.

Last year, Malaysian state-owned Petronas started production at its Kasawari gas field off Sarawak near Luconia Shoals, the site of previous tensions between Beijing and Kuala Lumpur. China Coast Guard and Chinese maritime militia presence aside, Vietnam and Malaysia accomplished specific objectives in the South China Sea without fanfare.

In contrast, tapping the oil and gas of Reed Bank remains an elusive goal for the Philippines, even as its biggest natural gas field, Malampaya, will soon be exhausted. The biggest infrastructure upgrade of Thitu Island and other Philippine-administered features ironically occurred during the previous Duterte government when relations with China were friendlier.

Manila has much to learn from its Southeast Asian neighbours if it wishes to go beyond marginal or symbolic victories like resupply missions to Second Thomas Shoal, documenting Chinese intrusions in its waters, Google displaying “West Philippine Sea” in its maps or having more countries joining its military drills. China’s presence in the Philippine exclusive economic zone is a concern, but China is not an existential threat.

China will always be bigger in all metrics. But negotiating with a big player does not always mean the small player leaves empty-handed. Hanoi, Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur deal with China on their terms with more confidence than Manila.

The Philippines should have clear interests and be persistent in pursuing them. One can argue that Vietnam and Malaysia capitalised on Manila’s noise to drive hard bargains with China, which yielded to avoid fraying ties with more pragmatic neighbours.

As long as other claimants can still get what they want, the bar for following Manila’s lead will remain high. Other Southeast Asian countries will refrain from engaging in name-and-shame campaigns or conducting megaphone diplomacy with China.

They think the costs outweigh the gains. Three years of Manila’s experience have informed them. While the goals may be similar, different approaches make for different results.

Philippines-China ties are at historic lows. Last year saw unprecedentedly violent sea incidents. In April, China arrested three Filipinos on espionage charges, a move seen as retaliation for a series of similar Philippine arrests of Chinese nationals. Both sides must recognise that ties have hit the floor – there is nowhere to go but up. In marking their 50th anniversary, both countries must do more to restore stability and expand cooperation.