Asean-GCC-China partnership can kick-start shift away from US-centric trade

The partnership offers a chance to reduce US reliance through new supply chains, trade agreements and regional production in critical sectors

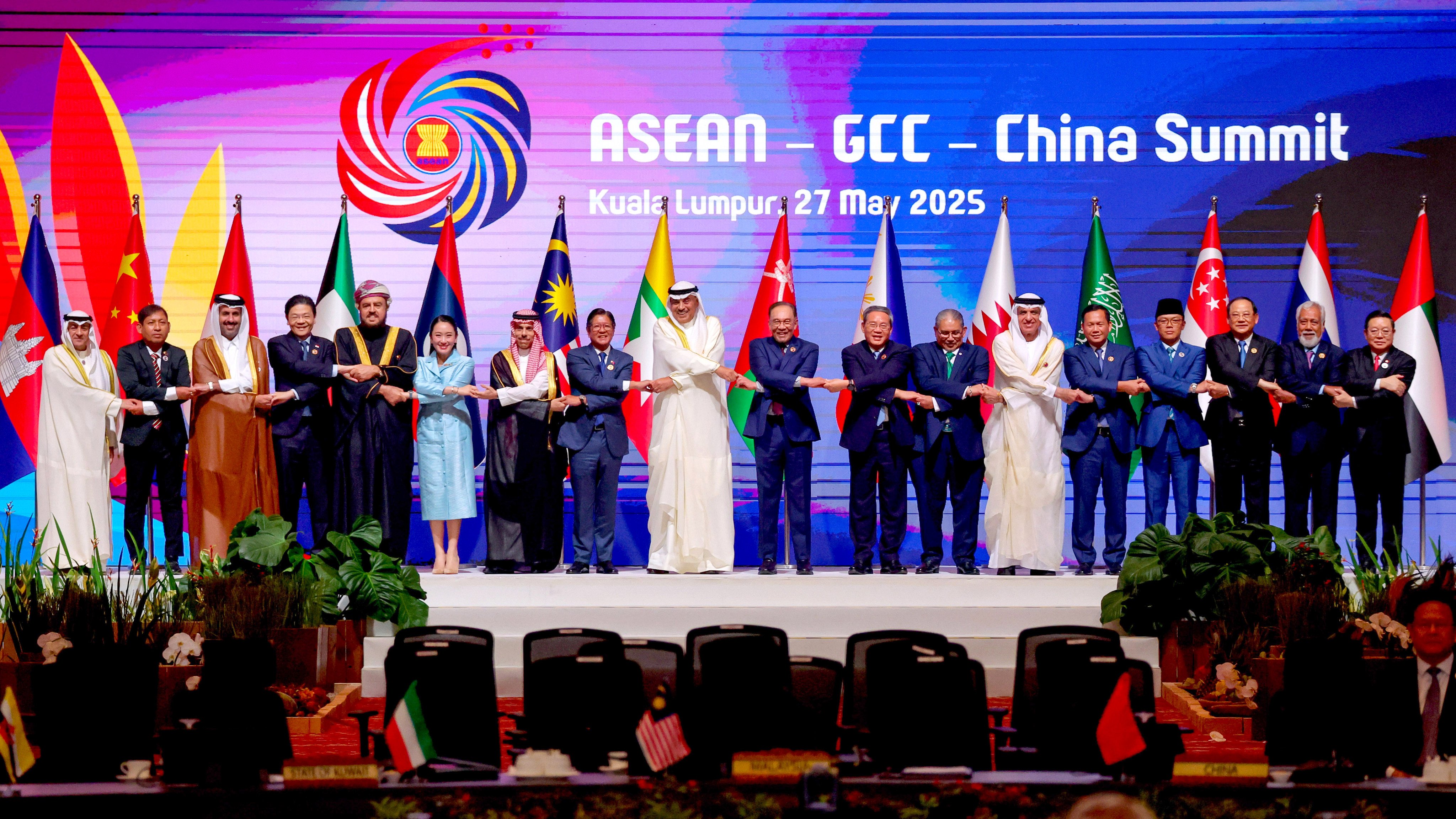

When the leaders of Asean, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and China gathered for an inaugural summit in Kuala Lumpur last week, it marked a historic convergence – the three economic powerhouses represent over 2 billion people and a combined economy of nearly US$25 trillion.

Emphasising deeper cooperation in trade, supply chains, infrastructure and finance, the summit’s key areas of focus included green energy, the digital transformation, connectivity and sustainable agriculture to address climate change and food security.

This trilateral partnership aligns with China’s Belt and Road Initiative, leveraging the consumer markets of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the GCC’s energy wealth and China’s manufacturing and technological prowess. With Asean-China trade worth US$1 trillion and GCC-China trade of over US$288 billion last year, the summit underscored a collective ambition to foster regional stability and economic globalisation, with vast potential for trade expansion.

It is also a transformative opportunity to reduce their reliance on the US market by diversifying supply chains and focusing on complementary strengths, enhanced connectivity, trade agreements and regional production in critical sectors.

First, Asean’s resources, the GCC’s financial clout and China’s manufacturing dominance constitute complementary strengths that can forge a robust supply chain ecosystem. Raw materials such as Indonesia’s nickel and Malaysia’s palm oil complement China’s manufacturing capacity, while the GCC’s sovereign wealth funds, worth a collective US$5 trillion, can finance critical projects.

Cooperation has begun. In April, the Qatar Investment Authority and sovereign wealth fund Danantara Indonesia announced a joint US$4 billion fund to invest in renewable energy, healthcare and technology in Indonesia. A practical model could see Asean supplying raw materials for China’s electric vehicle battery production with GCC funding.

Second, infrastructure projects can be a focus in advancing regional economic integration, something China has experience in, given its Belt and Road Initiative.

The GCC’s energy and halal food markets can be better connected with Asean and China, for instance, while the Gulf states, with their expertise in energy logistics, can be a helpful integration in Asean’s maritime trade routes, with the Malacca Strait alone handling 25 per cent of global shipping.

The benefits of deeper connections are known: an ambitious multinational project is under way to build a 21,700km submarine cable system between Singapore and France, crossing Egypt through terrestrial cables. Similar trilateral infrastructural investments can boost Asean’s digital economy, which is set to triple to US$600 billion by 2030, and help integration with China’s digital payment systems and the GCC’s Islamic finance networks, creating a robust digital ecosystem.

Asean requires at least US$2.8 trillion from 2023 to 2030 for infrastructure investment, according to the Asian Development Bank – this presents opportunities for the GCC’s wealth funds. Coordinated policies like tax incentives for green tech would maximise returns.

Third, strategic trade agreements can harmonise standards for localised production. The Asean-China free trade agreement is being updated but Asean and the GCC have only just embarked on a framework of cooperation.

Free trade agreements like the one between Singapore and the GCC, as well as the comprehensive economic partnership agreements such as those between the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia and Indonesia can serve as models for an Asean-GCC deal.

Among other things, aligning halal standards and standardising regulations for joint ventures in semiconductors and renewable energy projects could further boost Asean-GCC trade, already projected to be worth US$757 billion by 2030.

Asean’s fragmented regulatory frameworks and China’s overcapacity in certain sectors could lead to trade imbalances if not addressed. A trilateral task force could harmonise standards and ensure equitable benefits.

Fourth, facilitating investments in areas of comparative advantage can amplify economic gains. Asean’s labour-intensive manufacturing – Vietnam exported US$126 billion worth of electronics last year – complements China’s hi-tech sectors and the GCC’s capital surplus. Joint investment funds could target EV production, renewable energy and halal food processing.

For instance, Malaysia’s halal exports, worth 61.79 billion ringgit (US$14.51 billion) last year, could scale up with GCC investment in processing plants, while China’s 5G expertise could modernise Asean’s logistics.

However, navigating US dominance in defence, technology and market access poses a delicate challenge. Asean and the GCC states that are reliant on US military partnerships and tech supply chains must reduce their dependency cautiously.

The US remains the dominant leader in the global semiconductor intellectual property market, which is critical to Asean’s electronics and China’s tech ambitions. Strong US defence cooperation with Gulf states, as seen from the recent US$142 billion US weapons deal with Saudi Arabia, also complicates diversification efforts.

But strategic investments in non-weaponisable sectors, such as China’s investments in Asean’s clean energy projects – over US$2.7 billion between 2013 and 2023 – offer a path forward. Paths of cooperation could be found between Saudi Arabia’s US$10 billion investment push for green hydrogen and China’s solar panel manufacturing dominance.

A prudent approach involves gradual diversification, leveraging frameworks like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the belt and road to build alternative tech and energy ecosystems.

This trilateral partnership is more than an economic strategy; it is a bold declaration of agency in a world tethered to Western markets. By weaving together Asean’s dynamism, the GCC’s wealth and China’s innovation, this potential bloc can pioneer a multipolar trade order that prioritises resilience over dependence.

Amid rising protectionism and geopolitical flux, the Kuala Lumpur summit laid the foundation for a future where regions dictate their economic destiny, unshackled from US-centric constraints.

Riaz Khokhar is an MA political science candidate at the University of Gothenburg