South Korea’s ‘Warmth Mailbox’ delivers handwritten hope in an age of digital loneliness

The project sees volunteers answer letters from anonymous strangers with pen, paper and empathy

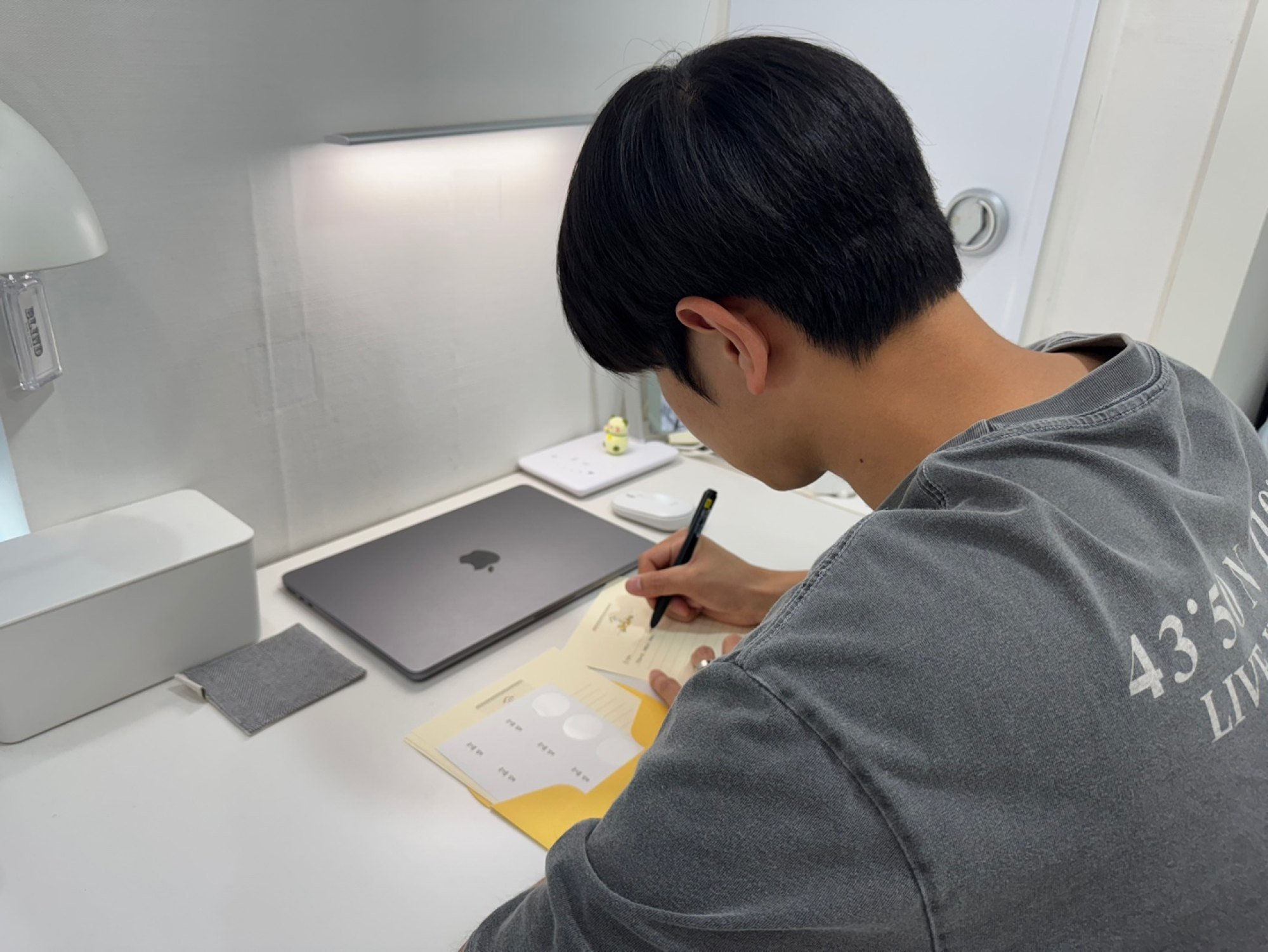

Every night, 25-year-old student Jeong Seung-won sits at his desk, pen in hand, reading scanned images of handwritten letters posted on a website called Ongi Woopyeonham – Korean for “Warmth Mailbox”.

The letters come from anonymous strangers: teenagers overwhelmed by school, retirees struggling with loneliness, or others simply seeking someone to listen.

“It’s a compilation of people’s fears, concerns and deepest regrets,” Jeong said.

But what makes Warmth Mailbox more than just a place to vent is what comes next: each letter receives a two- to three-page handwritten reply from a trained volunteer, like Jeong, offering empathy, reflection and, most of all, connection.

Launched in 2017 by Seoul-based charity Ongi, the Warmth Mailbox project has spread across the country, with more than 80 drop-off points installed in coffee shops, cinemas, parks, hospitals and university campuses.

In a hyper-competitive digitally driven society like South Korea – where therapy still carries a stigma – this analogue movement is gaining momentum as an unlikely remedy for emotional isolation.

“People write about a wide range of things. About 30 per cent of writers give us positive feedback after receiving a response from our volunteers,” said Cho Hyun-sik, founder of Ongi. “They say they find comfort in the idea that there is a place that will listen to their troubles, no matter what.”

Country under pressure

South Korea has the highest suicide rate among member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Particularly alarming is the fact that, as of 2023, suicide remains the leading cause of death among Koreans in their teens, according to Statistics Korea.

Surveys also consistently show a rise in depression and anxiety, especially among the young and the elderly.

“In South Korea, the idea of what constitutes a ‘good life’ is very standardised. People’s lives are judged by socially agreed-upon markers: appearance, academic success, competence, and wealth. When they fall short of those expectations, they may experience a sense of relative deprivation, which can lead to depression or anxiety,” said Kim Hyewon, a psychologist, counsellor, and professor at Hoseo University.

Kim says stigma around therapy still lingers in South Korea, though less than in the past. “There’s a clear generational divide,” she noted. “Younger people are more open to seeking help, whereas older generations still often hesitate.”

“Not everyone in South Korea has access to therapy,” Kim said. “Warmth Mailbox is a smart initiative that lets people open up without fear of judgment or criticism.”

Writing as therapy

The premise of the project is simple: write a handwritten letter detailing your struggles, seal it in a yellow envelope, and drop it in a Warmth Mailbox. Volunteers then retrieve the letters and write a personal, handwritten response – always at least two pages long.

“I was really stressed when I first started college. I didn’t think my studies suited me, and I had a hard time establishing new relationships,” said Emily Kim, a 20-year-old student who mailed a letter on October 19, 2023. “I felt aloof and empty.”

“I didn’t expect a reply,” she added. “But I received a two-page letter from someone older who had gone through similar struggles. It moved me deeply.”

“I felt like I was not alone – that some people went through similar things,” Kim said. “I think I felt great comfort and warmth. It was a healing experience.”

The exchange is just as transformative for volunteers like Jeong.

“As I relate to the writer’s troubles, and I think about similar experiences, I think it helps me round my character and become a more mature person,” Jeong said.

Kim, the psychologist, says that the project is mutually beneficial to all parties involved.

“Knowing that someone genuinely cares, conveyed through a thoughtful handwritten letter, can be deeply healing for people in pain or struggling with loneliness,” Kim said. “At the same time, volunteers benefit as well – they gain a sense of self-worth by reflecting on their own experiences and helping someone else.”

Empathy, not advice

Volunteers like Jeong undergo training sessions and workshops on trauma-informed writing and setting emotional boundaries. Each week, he writes one thoughtful response – usually at his home or at a quiet coffee shop where he can clear his mind and collect his emotions.

Cho, the nonprofit’s founder, also writes one letter each month. He recalls a case where a mother mailed a letter addressed to her recently deceased son.

“We had a postbox set up in a memorial space for young children who had passed away. A mother wrote a letter to her son and mailed it to us there,” Cho recounted. The volunteers replied to her as if they were the child, offering comfort and reassurance.

“The mother recently wrote us feedback saying that now, writing to her child through us has become her greatest source of comfort,” Cho said.

The letters are never clinical or prescriptive.

“We specifically train our volunteers to never offer an answer,” Cho said. “What we seek is sympathy based on experience, and sympathy that leads to consolation.”

From letters to a movement

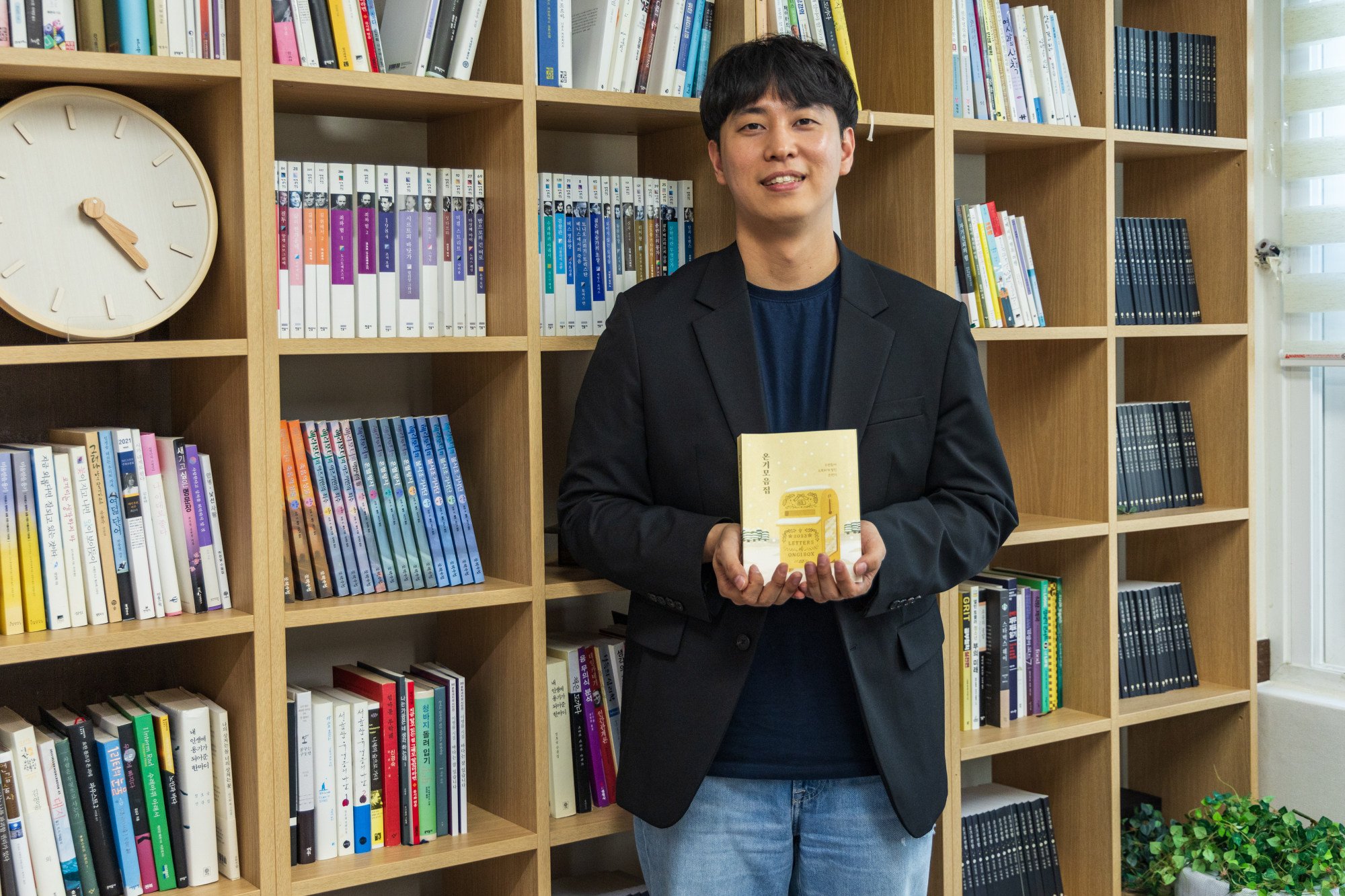

Cho created Ongi as a senior in college, envisioning a “psychological net” to help catch those falling into depression.

“It started out with just a few volunteers and me writing letters at a cafe,” Cho said. “When funding was low, I had to work as an IT developer during the day and write letters in the evening.”

Today, the project boasts 800 volunteers nationwide and replies to more than 20,000 letters annually.

The inspiration for the Warmth Mailbox came from the 2012 Japanese novel Miracles of the Namiya General Store, in which delinquents reply to anonymous advice-seeking letters dropped off at an old store.

“I wondered if something like that would be possible in real life,” Cho said. “Our society is becoming more depressed, and mental health is worsening. I thought having just one place that would sincerely listen to your troubles could help alleviate that.”

Growing community of warmth

As the project expands, Ongi is experimenting with pop-up booths and corporate collaborations. The group has partnered with South Korea’s largest cinema chain, CGV, to install postboxes in its theatres.

But Cho wants the idea to spread beyond Korea’s borders.

“We really want this Warmth Mailbox to become a movement,” he said. “We’d like other countries and organisations to benchmark our model and use it as a solution.”

“We are more than happy to provide our manual so that this postbox can also be operated elsewhere to combat depression and improve mental health.”

“The people who write these letters, they can be anyone, from the person you saw on the bus to someone you passed by on the street. The people who write and the people who reply – they’re all just average Joes,” Cho said.

“Everyone is so isolated these days. But because these letters are sincere, they allow people to really connect.”

Back in his flat, Jeong carefully seals another envelope.

“I don’t know this person, but I just hope they’ll feel better,” he said.

“It’s not like I want to change society, but it saddens me that the world is so full of hate nowadays. I just hope the people around me can have the warmth to see the world’s beauty. That’s why I participate in this project.”