Silicon rally: can Malaysia reclaim its semiconductor glory?

Outpacing regional chip rivals won’t be easy for ‘Silicon Malaysia’, but insiders say it has the subsidies, labour and will to succeed

In the northern state of Kedah, Malaysia’s hopes of climbing the semiconductor value chain stretch across thousands of acres of flatlands, cleared and primed for industrial estates.

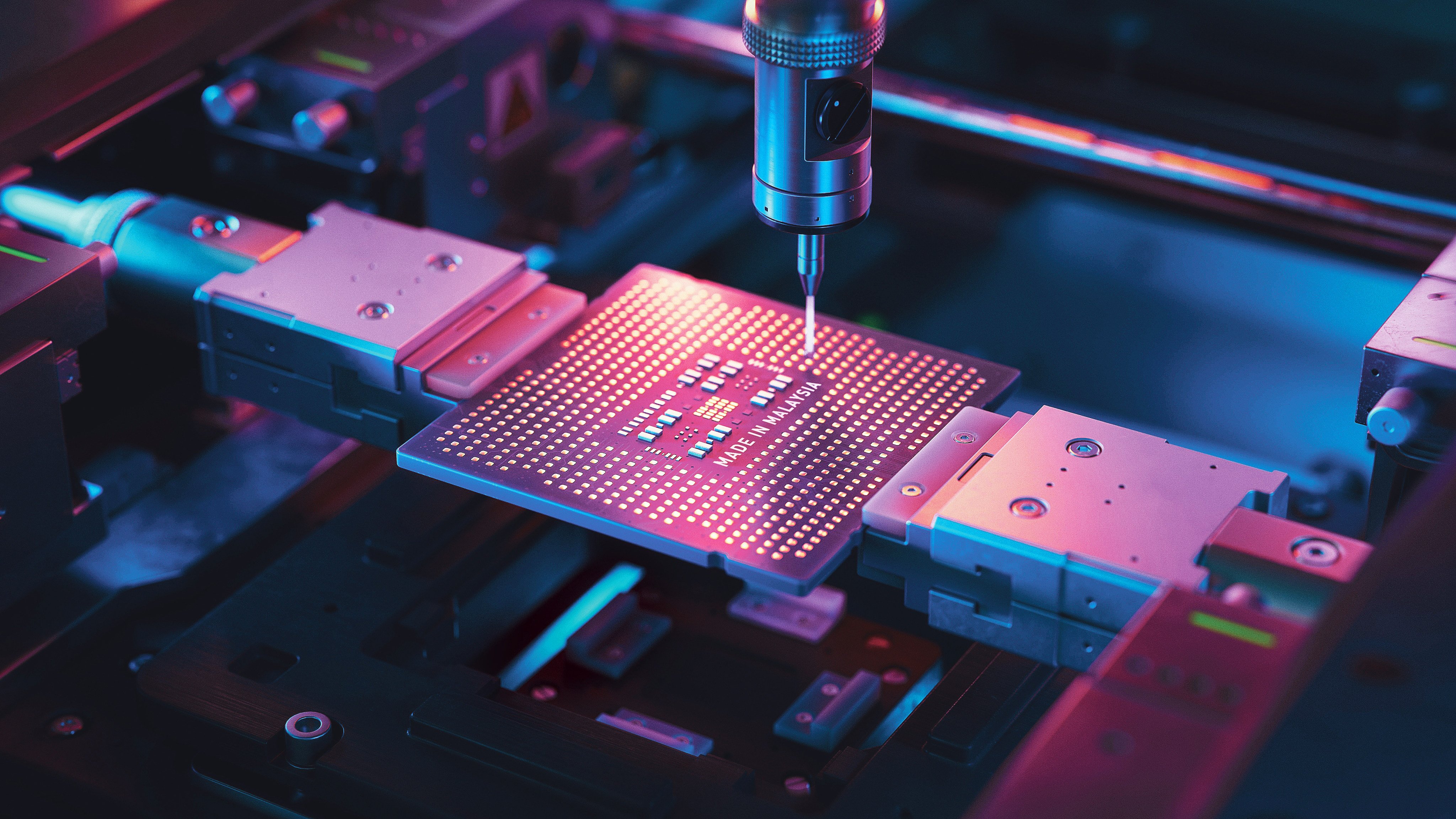

Inside cavernous production facilities, machines hum as they transform chemical compounds and electronic components – some as thin as a strand of hair – into the micro miracles powering smartphones, supercomputers and artificial intelligence (AI) that are coveted by militaries and tech firms alike.

Malaysia may only be the fourth-largest economy in Southeast Asia, but it punches far above its weight in semiconductors, ranking as the world’s sixth-largest exporter.

Better known as chips, these fingernail-sized pieces of silicon are the beating heart of modern technology – and Malaysia refuses to be left behind in the race for dominance.

The country’s strength lies in combining multiple chips into central processing units and graphics processors, a multibillion-dollar industry that took root in 1972 when US tech giant Intel opened its first overseas facility in Penang.

But Malaysia’s early head start has eroded over the decades. Corruption and political instability dimmed its economic ambitions just as the global competition for semiconductor supremacy began to heat up. Thailand, Vietnam and most recently Indonesia have emerged as alternative regional hubs, threatening Malaysia’s position.

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim is determined to reverse this trend. His vision? To regain Malaysia’s primacy in Southeast Asia and then break into the lucrative world of front-end chip manufacturing and design. To achieve this, his government has pledged to slash red tape, offer cheap land and provide power and water subsidies to attract semiconductor investors.

Poor but land-rich Kedah, long overshadowed by its industrial neighbour Penang, is central to Anwar’s plan to revitalise “Silicon Malaysia”.

But US President Donald Trump’s threatened tariff on Malaysian exports – set to rise to 24 per cent from early July – has created uncertainty, with mixed messages over levies for the semiconductor and electronics sectors.

Most companies are now preparing for the worstWong Siew Hai, Malaysian Semiconductor Industry Association on US tariffs

On Tuesday, the US Department of Commerce scrapped an “AI diffusion rule” introduced by former president Joe Biden that was set to take effect on Thursday and would have limited access to US-made AI chips to many countries, including US allies.

This came a day after the US and China had agreed to a 90-day pause on their tariff war, causing markets to rally and inflating the value of the world’s largest tech firms by more than US$800 billion, according to estimates by US news outlet CNBC.

Observers expect the Trump administration to replace Biden’s diffusion rule with separate agreements negotiated directly with individual countries – while maintaining stringent controls on shipments to China – creating further headaches.

“Most companies are now preparing for the worst,” said Wong Siew Hai, president of the Malaysian Semiconductor Industry Association.

“The tariffs will increase costs and very likely inflation. Global demand will slow down. When global demand slows down, everybody is affected.”

A recent survey of association members found that most expected US trade policy to hurt profitability and drive down investments, at least over the next year.

Still, with competing Southeast Asian chip hubs facing similar tariff pressures, Malaysia might just need to ensure it loses less to get ahead.

“I expect there will be more exemptions in the coming months as the impact of tariffs begin to hit American consumers,” said Cassey Lee, a senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore and coordinator of its regional economic studies programme. “They will progressively try to reduce the impact,” he said, citing the tariff carve-outs for tech that Trump announced last month.

“Carefully managing the expectations of foreign investors at the start of the conversation would go a long way” towards setting minds at ease, added Adib Zalkapli, managing director of geopolitical and public affairs firm Viewfinder Global Affairs.

Analysts say the challenge for Malaysia will be maintaining momentum, scaling up sustainably and capitalising on its existing ecosystem despite global headwinds.

“When the dust settles” on the tariff wars, Malaysia needs to have moved up the value chain so it is “the country that stands out in terms of tech advancements, capabilities, training of personnel”, Wong said.

“We need to do it now, so we become the country of choice for future tech and expansion.”

Kedah calling

In Kulim, Kedah’s westernmost district bordering Penang, the groundwork for future success is already being laid.

Austrian tech giant AT&S has invested around US$1.2 billion in a state-of-the-art facility at Kulim Hi-Tech Park, where its seven-storey production base manufactures high-end substrates – a key component in chip fabrication.

Launched in April, the facility is expected to reach full operational capacity next year, creating 3,000 jobs. AT&S is banking on Malaysia’s expanding ecosystem of data centres, which store the vast quantities of information required for AI.

“The government … said they want to attract data centres, which is good for us. They also said they want to train 60,000 engineers, which will help us as well,” said Yap Suan See, AT&S’ senior vice-president and managing director for Malaysia.

The Kulim facility is AT&S’ newest factory outside China, a strategic move to hedge against risks from Washington’s trade war with Beijing. Initially set up to supply US chipmaker AMD’s Penang facilities, the Kulim plant is now being positioned as a hub for customer and product expansion in AI and high-performance computing.

“It has the right infrastructure, it’s so near the Penang microelectronics hotspot, it has the staffing, labour, subsidies,” Yap told This Week in Asia. “It has the ecosystem.”

The company says it expects to sign two additional customers by the end of this year and two more by 2027 – all players in the AI space that are mostly already set up in Malaysia.

But challenges to future success remain. Investors often bemoan Malaysia’s labyrinthine bureaucracy and the lack of clear communication between federal and state agencies.

“Support we get, yes, but you always wish it could be faster,” said Ingolf Schroeder, AT&S’ executive vice-president for microelectronics.

Bottlenecks aside, Malaysia has been aggressively securing itself a place near the top of the global semiconductor pecking order. The government has announced grand plans to attract at least 500 billion ringgit (US$116 billion) in semiconductor investments, and more than 50 data centres, including those of Chinese tech giants ByteDance, Alibaba – owner of the South China Morning Post – and US chipmaker Nvidia now operate in the country.

It has not all been smooth sailing, however. Intel has delayed a 7-billion-ringgit (US$1.6 billion) expansion of its Penang operations due to slowing sales and mounting losses, while Austrian-German sensor manufacturer Osram pulled out of a 2-billion-ringgit factory deal last year after losing a key client.

Meanwhile, regional rivals Thailand and Vietnam have ramped up the pressure, attracting billions of dollars in investments from major players such as Intel, Infineon, Samsung and Sony.

But Malaysia is fighting back. In March, the government signed a US$250 million, 10-year deal with UK semiconductor design firm Arm Holdings, which creates the technology behind nearly all of the world’s smartphones – promising direct access to cutting-edge designs and technology for Malaysian firms.

“These chips will be designed, manufactured, tested and assembled here, and sold to the rest of the world,” said Prime Minister Anwar at the time, describing the initiative as the dawn of Malaysia’s “second semiconductor wave”.

Industry uncertainty

As chip factories and data centres mushroom across the Malaysian peninsula’s west coast, however, clouds of uncertainty are also gathering over the semiconductor sector.

In March, authorities in Singapore and the US launched investigations into allegations that advanced Nvidia chips had been illegally routed to China through Malaysia. Washington has since doubled down on export curbs, heavily restricting the sale of Nvidia’s H2O AI chips to China, citing national security concerns.

In response to US pressure, Malaysia has vowed to tighten regulations, pledging to track semiconductor shipments more closely and treat violations of export rules as a “serious offence”.

But the geopolitical chessboard continues to shift, with US lawmakers drafting legislation to clamp down on smuggling and prevent American chips from fuelling China’s military and AI ambitions.

Companies like Apple, which has pledged US$500 billion to relocate some manufacturing back to the US, are already aligning with Washington’s demands.

“Deadlines have often served more as strategic pressure points than immovable endpoints for Trump,” said Bryan DeAngelis, partner and head of the Washington office for global risk and analytics consultancy Penta Group. “Apple is a high-profile example, but the impact of Trump’s policies will be broader and affect many industries.”

Tariffs and trade wars will continue to be a concern for the industry, but AT&S’ Schroeder sees chip demand being fuelled by the breakneck growth of AI for years to come.

“If you believe that AI is going to be the driver of growth, most probably there will not be a downside [from tariffs],” he said.