In India, boycott calls against Turkey, Azerbaijan reflect growing ‘consumer-led diplomacy’

From traders to travel platforms, Indian companies are using economic tools to signal foreign policy displeasure, analysts note

Calls to boycott Turkish and Azerbaijani products and travel have intensified across India, with experts describing the push as an emerging form of consumer-led diplomacy in response to the two countries’ support for Pakistan during recent cross-border hostilities.

While analysts said the economic fallout for either side might be limited, they suggested the backlash reflected deeper shifts in Indian public opinion – and the country’s evolving use of economic tools to signal foreign policy displeasure.

“Backlash against Turkey and Azerbaijan is not merely a display of nationalism – it reflects a growing wave of consumer-driven diplomacy,” said Robinder Sachdev, founder president of the Imagindia Institute, a New Delhi-based independent think tank.

“This civic assertiveness is evident in actions by Indian online travel platforms and trade bodies, transforming public emotion into a form of soft economic leverage.”

The diplomatic rift follows India’s launch of “Operation Sindoor” on May 7, a military campaign that targeted nine alleged militant camps in Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir in response to an attack that killed 26 civilians in the Jammu and Kashmir town of Pahalgam. Islamabad denied supporting the groups involved and later retaliated, leading to escalating tensions along the border.

India also accused Pakistan of deploying Turkish-made drones during the conflict, prompting further public anger.

In the wake of these events, traders across India have begun rejecting Turkish goods such as apples and marble. The Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT) called for a complete boycott of Turkish and Azerbaijani goods and travel.

“The economic pressure could force both Turkey and Azerbaijan to reconsider their policies towards India,” said Praveen Khandelwal, CAIT secretary general and member of parliament.

The final decision on suspending trade with these countries will be taken at the trade leaders’ national conference on Friday in Delhi.

India and Turkey signed a bilateral trade agreement in 1973 to promote trade between the two countries. India’s exports to Turkey stood at US$5.2 billion from April 2024 to February this year, while imports from Azerbaijan were US$1.93 million in the same period.

India’s online travel platforms, such as EaseMyTrip and Ixigo, also issued advisories against visiting Turkey and Azerbaijan, citing security risks and political tensions.

According to government estimates, about 300,000 Indian tourists visited Turkey in 2023, and more than 200,000 travelled to Azerbaijan. India also maintains a small expatriate population in both countries – about 3,000 nationals, including 200 students, live in Turkey, while Azerbaijan hosts more than 1,500 Indians.

Subhash Goyal, tourism committee chairman at the Indian Chamber of Commerce, urged the government to issue a formal travel advisory for Indian citizens against visiting the countries.

India’s most prestigious university, Jawaharlal Nehru University, also suspended its memorandum of understanding with Turkey’s Inonu University, citing national security considerations.

Analysts say the economic fallout could hurt Turkey more than India. Ankara runs a trade surplus with Delhi, particularly in sectors such as construction materials, processed food and chemicals.

If Indian companies – both public and private – begin to diversify away from Turkish suppliers, exporters in Turkey could face real setbacks, especially given the country’s already difficult economic climate, according to Sachdev.

“In Azerbaijan’s case, economic ties with India remain limited, with imports amounting to just under US$2 million during April 2024 to February 2025,” he said. “As such, the friction is more symbolic than material.”

India’s discontent could influence energy partnerships and regional alignments, particularly as it strengthens ties with Armenia, Greece and Cyprus – countries that also have long-standing grievances with both Turkey and Azerbaijan, according to Sachdev.

While an outright diplomatic rupture appears unlikely in the near term, analysts say Delhi is expected to recalibrate its approach by delaying high-level engagements, quietly sidelining bilateral mechanisms and expanding strategic cooperation with Turkey’s regional rivals.

Companies are also likely to be among those affected.

“The reason [companies] are vulnerable is because of where they are from, or their corporate nationality. They are seen as an extension of their home country, whether they intended it this way or not,” Srividya Jandhyala, an associate professor of management at the ESSEC Business School in Singapore, told This Week in Asia.

“Reactions of governments, customers, suppliers and other stakeholders are not necessarily due to what the company does or how good its products or services are.”

In the short term, companies could face consumer backlash, with their products being targeted and sales potentially declining, Jandhyala said, adding that in the longer term “this backlash may intensify due to government policies and regulations”.

On the other hand, bilateral relations could sometimes normalise, and firms go back to doing business as usual, she noted.

Pushan Dutt, an economics and political-science professor at INSEAD business school, said the recent hostilities with Pakistan had ironically provided a “rude awakening” for India in terms of its perception of its global standing.

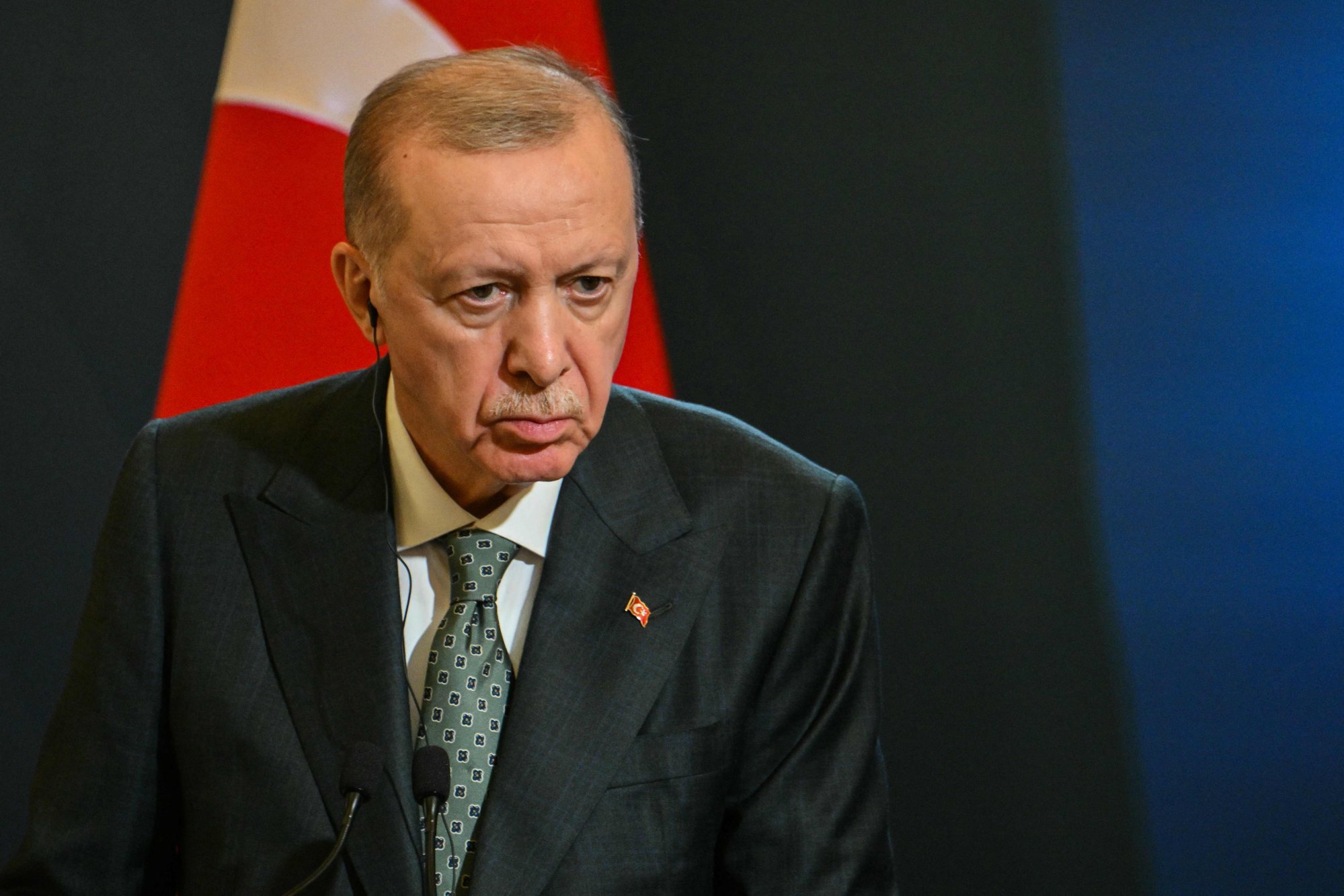

“[Turkish] President [Recep Tayyip] Erdogan recently referred to Pakistan as a ‘precious brother’. In the broader context, to India’s chagrin, no country unequivocally backed India’s asserted right to retaliate after the terrorist attacks,” Dutt said. “This has been a rude awakening for India and its standing in the geopolitical arena.”

Dutt noted that India lacked the economic influence which would have allowed it to effectively wield the trade carrot-and-stick to hit Turkey and Azerbaijan where it hurt most.

“Only 0.64 per cent of Turkey’s exports go to India, and 3 per cent of its imports are from India. Similarly, only 0.5 per cent of Turkey’s tourists come from India. Therefore, boycotting goods, trade and tourism will have only a small economic impact on Turkey and Azerbaijan,” Dutt said.

The main lesson India should draw, Dutt added, was that it would not be taken seriously unless it became globally more relevant in terms of trade, tourism and technology.

Harsh V Pant, a foreign-policy specialist at the Delhi-based Observer Research Foundation think tank, said Erdogan’s approach to the India-Pakistan clashes had hurt sensitivities in Delhi.

India on Wednesday briefly blocked the X handle of Turkish broadcaster TRT World for reportedly spreading misinformation, after the Ministry of External Affairs noted Turkey’s support for Pakistan during Operation Sindoor.

“In the heat of the moment, there is a lot of outcry [that] if Turkey is uninhibited in its outreach to Pakistan, why should India be inhibited in deciding the course of action against Turkey,” Pant said.

While the Indian government was not expected to end trade with Turkey, it could take certain diplomatic steps in managing the crisis, Pant said, citing the example of blocking TRT World.