‘Green menstruation’: Nepal’s activists tackle pad pollution for women’s health

A factory in Nepal is challenging traditional views on menstruation by educating the public about its biodegradable menstrual pads

In a quiet corner of southern Nepal, a small women-run factory is driving a growing movement to replace conventional menstrual pads with biodegradable alternatives – part of grass roots efforts to protect women’s health and the environment while dismantling entrenched taboos around menstruation.

The Miteri Jaibik Pad Udhyog (Miteri eco-friendly pad factory) in Chitwan district’s Gunjanagar has been manufacturing single-use biodegradable pads and reusable cloth pads since 2017, dispelling perceptions that such products are either costly or unhygienic.

Called Miteri – or “chosen kinship” in Nepali – the pads offer women healthier choices while raising awareness about the high environmental footprint of disposable non-biodegradable pads and encouraging what some advocates call “green menstruation”.

“I grew up seeing women use unhygienic cloths during menstruation,” said Radha Paudel, a nurse turned advocate for dignified menstruation, who started the pad factory along with Chitwan-based Active Women’s Forum for Justice. “I always wanted to start a social enterprise that upheld a menstruator’s dignity, that is good for the planet and also affordable.”

That philosophy is put into practice inside a tin-roof factory, where a single machine produces about 8,000 pads daily. They are made using pinewood pulp sheet and cotton, with bioplastic packaging, ensuring the entire product is biodegradable.

Calls to promote eco-friendly pads in Nepal come at a time amid growing concerns globally over the safe disposal of menstrual products. Several studies show that tampons and pads are made up of up to 90 per cent plastic and usually take 500 to 800 years to decompose.

In Nepal, an estimated 140 million pads are used annually, adding to a significant menstrual waste load in the country, according to research by Kathmandu-based Health Environment and Climate Action Foundation, or HECAF360.

Mahesh Nakarmi, founding chairman and executive director of HECAF360, said his organisation tested 47 brands of menstrual pads and tampons available in Nepal in 2018. They found that most non-biodegradable pads contained harmful chemicals such as super absorbent polymers and bleaches, while some commercially available fabrics contained chemical dyes.

“Our worm composting showed that pads made from cotton cloth and dyed with natural plant-based dyes, and single-use products made from plant-based fibres such as pine and banana, were the only ones fully consumed by worms within six months,” he said. “That’s good for the environment and also protects women from exposure to harmful chemicals found in non-biodegradable available pads – chemicals that global research has linked to serious health issues, including cancer.”

Nakarmi said their research found that most pads were either flushed, burned or end up in landfills in the absence of national guidelines for menstrual waste management. He added that while the government’s pad distribution programme in schools was well-intentioned, it must also consider the environmental impact and the long-term health of girls, which could be at risk if these issues were not addressed on time.

The Nepali government introduced a national programme to distribute free pads across schools in 2020, aimed at ensuring menstrual health and curbing absenteeism of girl students during their monthly cycle.

“We’re lobbying for a transition from single-use menstrual pads to reusable biodegradable alternatives and have held discussions with ministries and policymakers,” Nakarmi said. “But very few are paying attention. Currently, there is an insufficient supply of compostable, safe, single-use and reusable biodegradable pads in the market.”

Few local governments have made efforts to promote eco-friendly pads, including the Madi municipality, some 40km from Gunjanagar. Madi, which brands itself as an “eco village”, donated 500,000 rupees (US$3,685) to Miteri in 2021 and also bought the pads for its school distribution programme around the same time.

However, the initiative later ended due to procurement changes that favoured bulk orders, said municipality chief Shiva Prasad Subedi.

“We want to promote locally made and sustainable products,” he said. “An eco-friendly pad factory would add to our cause, though Miteri would need a bigger production to meet our demands. It would also contribute to the local economy.”

Inspired by Miteri’s initiative, other small enterprises are also taking the lead. Sparsa, another women-led social business, is introducing compostable pads made of banana fibre in Chitwan, utilising the region’s agricultural waste and generating employment.

Breaking down taboos

Anjana Kumal, a 32-year-old employee at Miteri’s facility, said her work had enabled her to speak out against a taboo topic. She even set an example by celebrating her 11-year-old daughter’s first menstruation last year while working at the factory instead of confining her as would have been the case under local tradition.

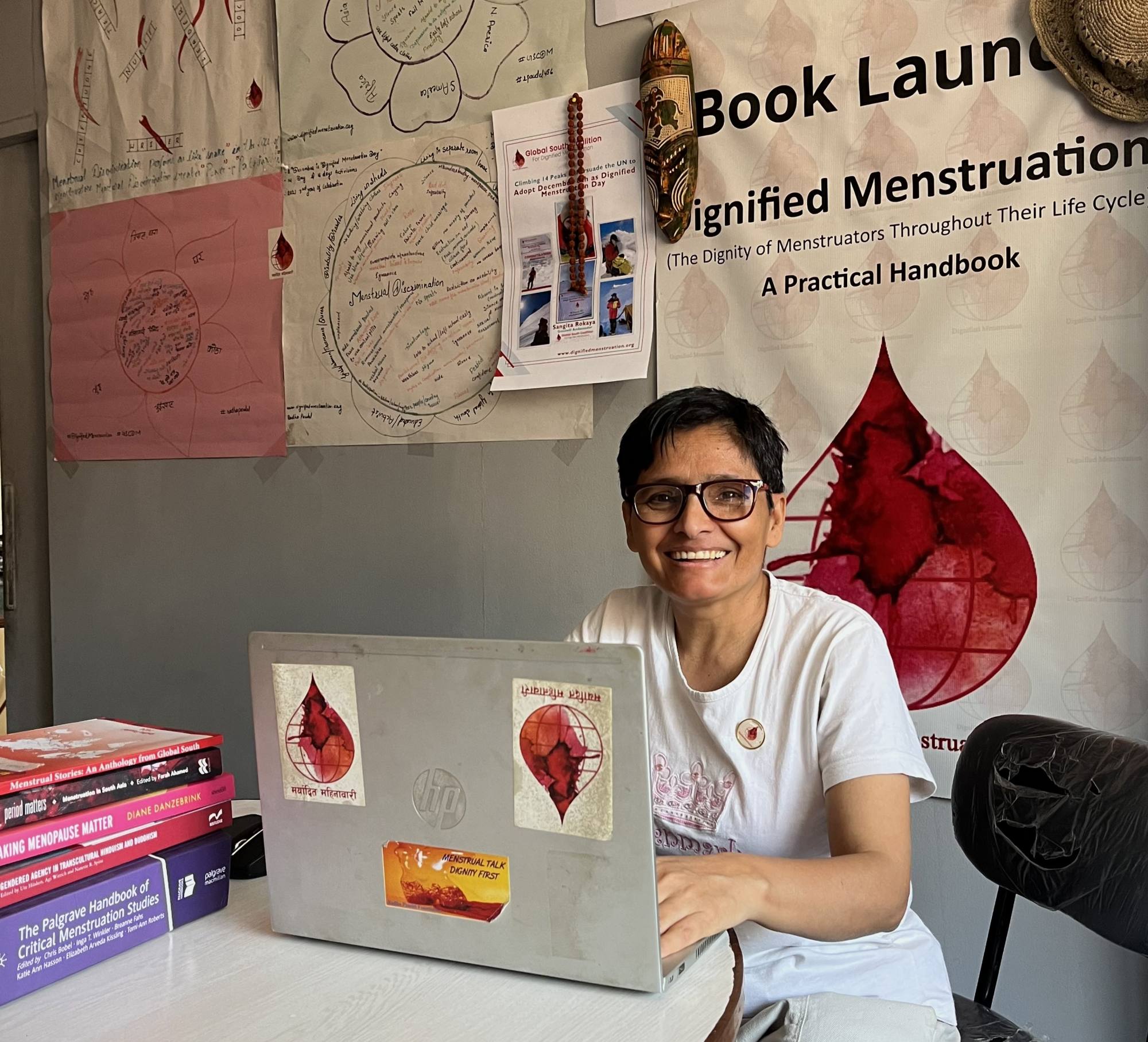

“Miteri provides not just entrepreneurial skills to marginalised communities, but turns women from victims and survivors of menstrual discrimination to community leaders,” said Paudel, also the founder of Global South Coalition for Dignified Menstruation.

Menstrual practices are deeply rooted in religion and culture in Nepal, with women referred to as “untouchable” during their monthly cycle. They are barred from entering kitchens, taking part in religious rituals and in extreme cases banished to menstrual huts, where women have been raped or died of snakebites and suffocation.

Nepal criminalised the practice of banishing women to huts in 2017, stipulating a three-month imprisonment or a 3,000 rupees (US$22) fine for violating the law. However, the practice has not been entirely eradicated.

Dila Datt Pant, a United Nations Development Programme official who works on women’s rights, said menstrual discrimination persisted as a cultural norm despite existing laws, which were often unenforced due to social acceptance. Laws alone, he noted, could not fix “entrenched cultural beliefs” without routine scrutiny and stronger implementation. In the absence of effective enforcement, schools and teachers are playing a crucial role in raising awareness about the issue.

The Shree Secondary School in Sashinagar, about 15 minutes away from the Miteri factory, has declared itself a “dignified menstruation-friendly” school. The school has a separate toilet for menstruating students, and its walls display poems challenging menstrual discrimination.

Female teachers who once discussed menstruation with girls behind closed classroom doors now openly show how to use pads to both girls and boys. They also educate students on the health and environmental aspects of menstrual products.

While Shree Secondary School once distributed biodegradable pads to students, it has switched to non-biodegradable ones despite having a dedicated disposable system. The school acknowledged the problem, with teachers saying biodegradable pads needed better visibility and marketing to make them more appealing to compete with widely used brands.

Moti Kumari Kandel, a teacher and member of the Active Women’s Forum for Justice, agreed that brands like Miteri lacked marketing due to limited resources, but she remained committed to changing the mindset of her students, colleagues and the wider community. When not teaching, she usually goes door-to-door advocating.

“We can’t just stop at speaking against menstrual discrimination now,” she said. “We should also talk about biodegradable pads, and the government should prioritise and support locally made products. It’s a matter of the health of our girls and women, and also the health of our environment.”