The end of ‘Chimerica’ and what that means for Southeast Asia

The breakdown of US-China economic symbiosis leaves Southeast Asian nations bracing for unpredictable shocks

US President Donald Trump’s decision to double down on tariffs on China while pausing escalation towards other countries may signify that the United States is entering the final stages of decoupling from “Chimerica” – the symbiotic relationship between the world’s two largest economies. However, the results of Trump’s approach so far suggest that a global economic restructuring in Washington’s favour is unlikely.

For Southeast Asian countries, this could result in a future characterised by unpredictable shocks. Despite the unpredictability of Trump 2.0, replacing US export markets, investments and technology inputs remains a difficult task. However, China is not only the fastest growing investor and leading trade partner for these nations but also possesses “escalation dominance” over the US in the ongoing trade war. Essentially, China is better equipped to withstand this conflict.

Exports are important but not critical to China, constituting around 20 per cent of gross domestic product, with the US now accounting for under 15 per cent of Chinese exports. The domestic drivers of China’s economy are evident in emerging sectors. China’s leading electric-vehicle maker BYD generates around 80 per cent of its revenue at home. Currently, an estimated 10 to 20 million workers in China are exposed to US export markets. In contrast, in the late 1990s, China’s state-owned sector laid off 35 million workers without causing national disruption.

The US is already expanding its restrictions beyond tariffs, prohibiting the export of critical goods to China. But China has developed import substitution efforts and methods to circumvent export control. In hi-tech sectors like chipmaking, China’s domestic industry generates almost all its revenue at home and can now meet many requirements independently, or source them from countries other than the US. China can also source agricultural and energy imports from third countries.

Unlike Trump’s erratic, incoherent, and seemingly improvised methods, China has long prepared for this situation. Beijing has expanded its export controls to leverage its dominance in minerals processing, most recently for rare earth elements. It is targeting US service imports like Hollywood films, and increasing non-tariff measures that affect US exports linked to politically significant constituencies in America.

Unsurprisingly, there is no sign of the deal-seeking from Beijing that Trump had apparently expected. Conversely, the US is already signalling at least a partial retreat.

Despite China’s economic challenges, its leaders know their country has advantages of scale over the US, particularly in global manufacturing, which hindered reshoring even before Trump’s global tariff escalation began. Over one-third of US imports from China are highly exposed to it as a sole-source country, while only 10 per cent of Chinese imports come from the US.

In many hi-tech and less complex manufacturing sectors, hollowed-out US workforces cannot yet support extensive homeshoring. Meanwhile, US industry must absorb tariffs passed on by foreign suppliers, including US multinationals that conduct much of their production abroad. US carmakers alone will potentially face US$108 billion in extra costs due to the Trump administration’s tariffs this year.

In the longer term, Trump’s methods are undermining the foundations of US dominance in trade and technology. This is particularly evident in US financial markets, which have been destabilised by the simultaneous sell-off of stocks, bonds, and the dollar. There are increasing concerns that the US dollar’s global reserve currency status is at risk. US scientists and engineers are raising alarms about the Trump administration’s politically driven “decimation” of the national research enterprise, leading a growing number of US-based researchers to consider job opportunities abroad.

These trends matter because US dominance in many hi-tech industries is more fragile than it first appears. In the semiconductor industry, for instance, US firms still account for most of global revenue. But much of this comes from software and chip-design activities that have relatively low barriers to entry. Leaders in these fields like Nvidia face rising competition from China and elsewhere. US vendors of chipmaking equipment face mature competitors in advanced economies and increasingly in China.

The global exclusions from US “reciprocal” tariffs announced on April 11 cover almost one-quarter of US imports from China by value. These exclusions focus on electronics, and seemed to benefit several Asean member states. But on April 14, the US announced an investigation into imports of semiconductors and chipmaking equipment, flagging potential new tariffs and quotas to drive import substitution. This could pose a threat to the semiconductor industries in Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam, which are crucial to their development plans and essential for emerging sectors like EVs.

Trump trade adviser Peter Navarro had singled out Vietnam for punishment, saying that Hanoi’s offer to drop tariffs to zero “means nothing”. Tariff reductions may be tied to issues beyond international trade that Trump and his subordinates want other countries to address, including value-added tax, digital economy governance and food safety regulations.

Renegotiating trade relations with the current US administration is likely to serve only as a damage-mitigation exercise, even if an agreement is reached within the 90-day tariff pause. Industry lobbying could undermine any such agreement, an example being the recent imposition of duties on solar panel imports from four members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in late April. Ongoing US-Japan negotiations have not provided an encouraging example of success.

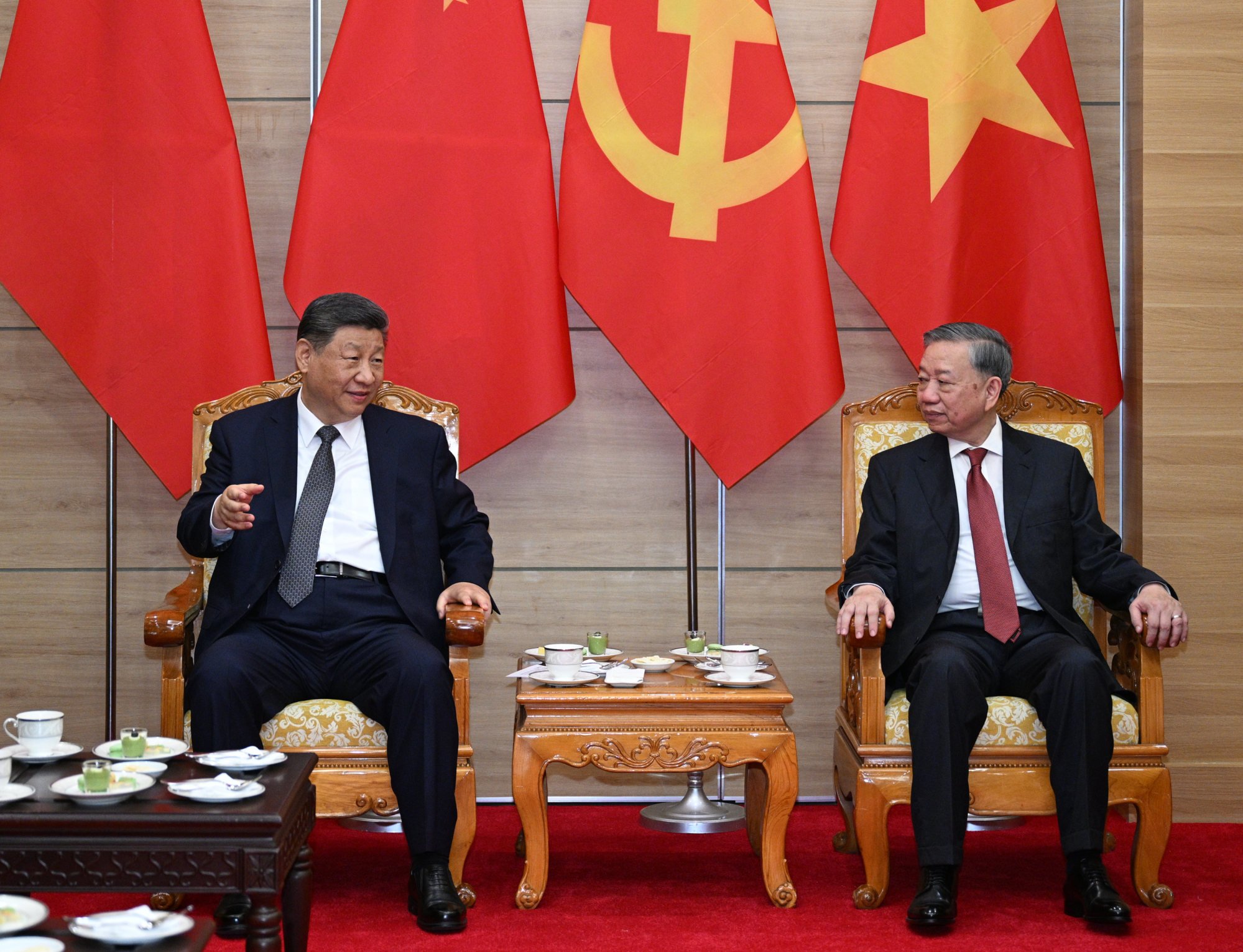

The clearest theme of Trump 2.0’s chaos is the intent to restructure economic relations with all countries asymmetrically in Washington’s favour. To hedge against this, the EU, UK, Japan, South Korea and Brazil are talking to China. Southeast Asian governments have made the right choice in doing the same. Although the current US government may interpret this as hostile, such reactions from Washington are now just a ‘new normal’ that must be managed.

John Lee is director of consultancy East West Futures, a researcher at the Leiden Asia Centre and was a Visiting Fellow with ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. This article was first published by ISEAS – Yusof Ishak’s commentary website fulcrum.sg.