Mahathir Mohamad on Trump, tariffs – and the end of America’s century

Malaysia’s 99-year-old two-time PM delivers a blunt assessment of America’s ‘empire’ mentality and its impact in an exclusive interview

The world is shifting, and with it comes an unsettling sense of uncertainty.

Once the undisputed leader of the post-war order, the United States now appears to resent its own dominance, lashing out at allies and adversaries alike. Donald Trump’s chaotic second term in the White House has been emblematic of this change. His erratic policies – lopsided “reciprocal” tariffs, threats to annex Canada and Greenland, and a strange cocktail of isolationism and imperial ambition – have left even America’s closest partners reeling.

Meanwhile, efforts to erode the US dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency have only added to the sense of an American empire in retreat.

Online, videos proliferate, all posing the same question: is this the end of the American century?

Trump is, in many ways, behind time; the age of empires is overMahathir Mohamad

Few figures alive today have witnessed the rise and fall of empires like Mahathir Mohamad. Born in 1925, in the shadow of the first world war, Mahathir grew up in rural Kedah, a Malaysian state then under Siamese suzerainty. He has lived through Japanese occupation during World War II, the break-up of the British Empire, and the ascendancy of first America, then China.

Now, as he approaches his 100th birthday in July, the two-time prime minister of Malaysia sees a familiar pattern playing out.

Speaking to This Week in Asia from his office in Putrajaya, Mahathir offered a blunt assessment of the US president’s second term and the world that America has reshaped:

“Trump is, in many ways, behind time; the age of empires is over.”

Polarising figures

Mahathir is no stranger to shaping history. Malaysia’s longest-serving prime minister, he held office for more than 24 years, transforming the country from an agrarian exporter of tin and rubber into a manufacturing powerhouse. Today, Malaysia produces semiconductors and electronics for both the West and China – a testament to Mahathir’s vision.

Yet his legacy is polarising. While celebrated for modernising Malaysia, critics accuse him of authoritarianism, a hallmark of Southeast Asia’s strongman era. His tenure remains a topic of debate in the country, where his place in history is still contested.

Unlike regional contemporaries such as Indonesia’s Suharto or Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Snr, Mahathir stands out as one of the few strongmen to voluntarily step down at the peak of his power – a rare feat in a region that is no stranger to tumultuous transitions.

Although he no longer wields political power, the elder statesman’s influence looms large. Just months away from becoming a centenarian, he remains sharp and deeply engaged with global affairs.

“Americans have a lack of perception of the realities of the world,” he said. “That has resulted in Trump behaving as if he has the right to take over other countries.”

Barely 100 days into his second term, Trump has already sparked a series of international crises – each as audacious as it has been destabilising. From renaming the Gulf of Mexico the “Gulf of America” to threatening Canada with annexation as the US’ 51st state, Trump has continually turned diplomatic norms on their head.

The fallout with Canada, once America’s closest ally, was swift and bitter. Blaming Canadian imports for the US’ fentanyl addiction crisis, Trump imposed harsh tariffs on Canadian goods, transforming neighbourly ties into open hostility overnight. Canada retaliated with visible defiance, labelling American imports in stores and calling for a nationwide boycott. Hockey fans booed the US national anthem and Canadian tourists cancelled their trips south of the border.

At the same time, Vice-President J.D. Vance fanned the flames in Europe, delivering a scathing lecture accusing the continent of undermining free speech and enabling mass migration – issues he framed as greater threats than an expansionist Russia. Trump’s No 2 later paid a controversial visit to Greenland, stoking speculation that Greenlanders might prefer American rule over their current status as part of the Kingdom of Denmark, while the US president himself reiterated his desire to take control of the island, by force if necessary.

In another throwback to the authoritarian bluster of America’s imperial past, Trump has also set his sights on the Panama Canal. More than two decades after the US handed control of the canal back to Panama in 1999 – a decision Trump has repeatedly derided as “foolish” – the US president is now threatening to take it back. Last weekend, he declared on social media that American military and commercial ships should enjoy unrestricted access to both the Panama and Suez Canals, asserting that neither would “exist without the United States of America” – seemingly unaware that the Suez Canal was constructed in the mid-19th century by a French-led company.

Yet it is Trump’s so-called reciprocal tariffs, unveiled on the grandiosely named “Liberation Day” of April 2, that have caused the most far-reaching damage so far. The tariffs, which take particular aim at Southeast Asia, have shaken global trade to its core.

For Mahathir, these tariffs and Trump’s other policies are an affront to everything the world has worked towards since the end of the second world war. “We are trying to break down borders, but he is building barriers,” Mahathir said.

The bulk of Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs, excluding those imposed on Chinese imports and a baseline 10 per cent levy on all other countries’ goods, were paused for 90 days not long after they were announced. If and when they come into force, US importers will be required to pay taxes ranging up to 49 per cent on goods from Southeast Asian nations.

Regionally, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and conflict-ravaged Myanmar were hit with the highest proposed tariffs, but not even US allies like the Philippines – which would be subject to a 18 per cent levy – were spared.

Singapore, one of the world’s most trade-dependent nations, escaped relatively unscathed. It still faces the universal 10 per cent tariff, however, prompting a rare public rebuke from Prime Minister Lawrence Wong, who expressed his dismay in parliament on April 8.

“We are very disappointed by the US move, especially considering the deep and long-standing friendship between our two countries,” Wong said. “These are not actions one does to a friend.”

Vietnam has led the scramble to mitigate the damage, offering concessions to Washington – some of which were brusquely rebuffed by Trump’s trade adviser – as other Southeast Asian nations, including Thailand and Indonesia, also tried their luck. Jakarta recently proposed reducing quotas and duties on US imports in a bid to escape the 32 per cent tariff that Trump has threatened to impose.

The region’s frustrations have spilled over into bitter humour. In Malaysia, some quipped that Trump’s tariffs had dragged Southeast Asia back to its pre-colonial days, when small, warring states were expected to send tribute in the form of gold and silver flowers hammered into intricate designs to the Thai king in Bangkok as a symbolic gesture of subservience.

Trump’s tariff blitz comes at a time when Chinese businesses, seeking to dodge earlier US levies, had already begun shifting operations to Southeast Asia. This migration fuelled rapid industrial growth in the region, cementing its role in global manufacturing supply chains.

To the mercurial US president, however, these countries are now complicit in helping China “cheat America” by serving as back-door exporters for Chinese goods.

‘You can’t stop China’

Mahathir sees Trump’s tariffs as part of a broader attempt to weaken China, but he is unconvinced it will succeed.

“It has the technology and capacity” to weather the economic slowdown, Mahathir said. “Its whole market is bigger than the combined market of Europe and America. So, China will grow. You can’t stop China.”

A long-time critic of Western foreign policy, Mahathir has repeatedly called for war to be outlawed internationally, arguing that armed conflict is too often used as a cynical tool for political and economic gain, wrapped in the rhetoric of freedom and democracy. In his view, the US’ escalating confrontation with China amounts to a war “short of going to war” in the conventional sense.

“The American idea is that they must remain No 1, so they are trying to stop China,” he said. “That means confrontation, sanctions, all kinds of things.”

Mahathir does not see Trump as a deviation from the norm, but a reflection of America’s deeper geopolitical instincts. Provoking conflict abroad, he argues, has long been a feature of US foreign policy.

He pointed to the highly publicised 2022 visit by then-US House speaker Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan – a visit that Beijing viewed as a blatant provocation. The trip triggered a massive show of force by the People’s Liberation Army, heightening tensions in the Taiwan Strait.

For Mahathir, this escalation served a distinct purpose. “When [mainland] China shows its military strength, America says Taiwan must rearm – and that means buying weapons from America,” he said. “So business-wise, the tension between Taiwan and [mainland] China is very good for America.”

Pelosi’s brief stopover in Kuala Lumpur before heading to Taipei also sparked a backlash within Malaysia. Critics accused then-prime minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob’s government of tacitly enabling Washington’s provocations. Even Ismail’s special envoy to China, Tiong King Sing, openly condemned the visit, drawing a parallel to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“On the one hand, [the US] condemns Russia, protests Russian aggression against Ukraine, and calls for Ukraine’s sovereignty,” Tiong said at the time. “But on the other hand, they intend to interfere in the internal affairs of the Taiwan Strait region and use Taiwan to divide [mainland] China.”

Fear vs injustice

Having lived through a global war triggered by Europe’s actions, Mahathir’s world view has been shaped by a deep scepticism of Western powers and their history of conflict. For him, “the love for war is a part of the culture of the European nations”.

“I studied European history, and it is all about European wars,” Mahathir said in 2022, shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine. “When the Chinese invented explosives they used it to frighten imaginary dragons. When the Europeans got the technology, you used it to kill more distant people with cannonballs, bullets, shells and rockets.”

While he has expressed sympathy for Ukraine’s struggle against Russian aggression, Mahathir has also courted controversy by suggesting that Kyiv should consider concessions to avoid further devastation. His perspective on the conflict is rooted in a long memory of Cold War dynamics and what he sees as missed opportunities for peace.

When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, Mahathir argued that the transatlantic security alliance Nato, like the Warsaw Pact, should have been dismantled. In his view, this would have created the conditions for genuine de-escalation and a stable post-Cold War order. Instead, emboldened by their victory over what ex-US president Ronald Reagan dubbed the “Evil Empire”, Western powers expanded Nato into former Soviet territories, stoking Moscow’s fears of encirclement and, ultimately, laying the groundwork for future conflict.

“This shows that it’s not just Trump – it’s the whole American system,” Mahathir said. “Even though they supported Ukraine, they didn’t join the war. They just told Ukraine: fight, and Ukraine has paid a very high price.”

The costs for Ukraine have been staggering. Since the war began in 2022, nearly 50,000 Ukrainian soldiers have been killed, with more than 380,000 wounded. Vast swathes of territory have been seized by Russia, while over 10 million people – one-quarter of Ukraine’s pre-war population – have been displaced, including roughly 7 million who have sought refuge in neighbouring countries.

As the war in Europe has raged, Malaysia has been quietly recalibrating – edging closer to Moscow’s orbit and signalling its intent to join Brics, the bloc of emerging economies often viewed as a counterweight to the G7. Neighbouring Indonesia became the latest Brics member earlier this year, joining founders Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and a raft of other nations in a bloc that now represents over 40 per cent of the world’s population and accounts for roughly one-third of its economic output.

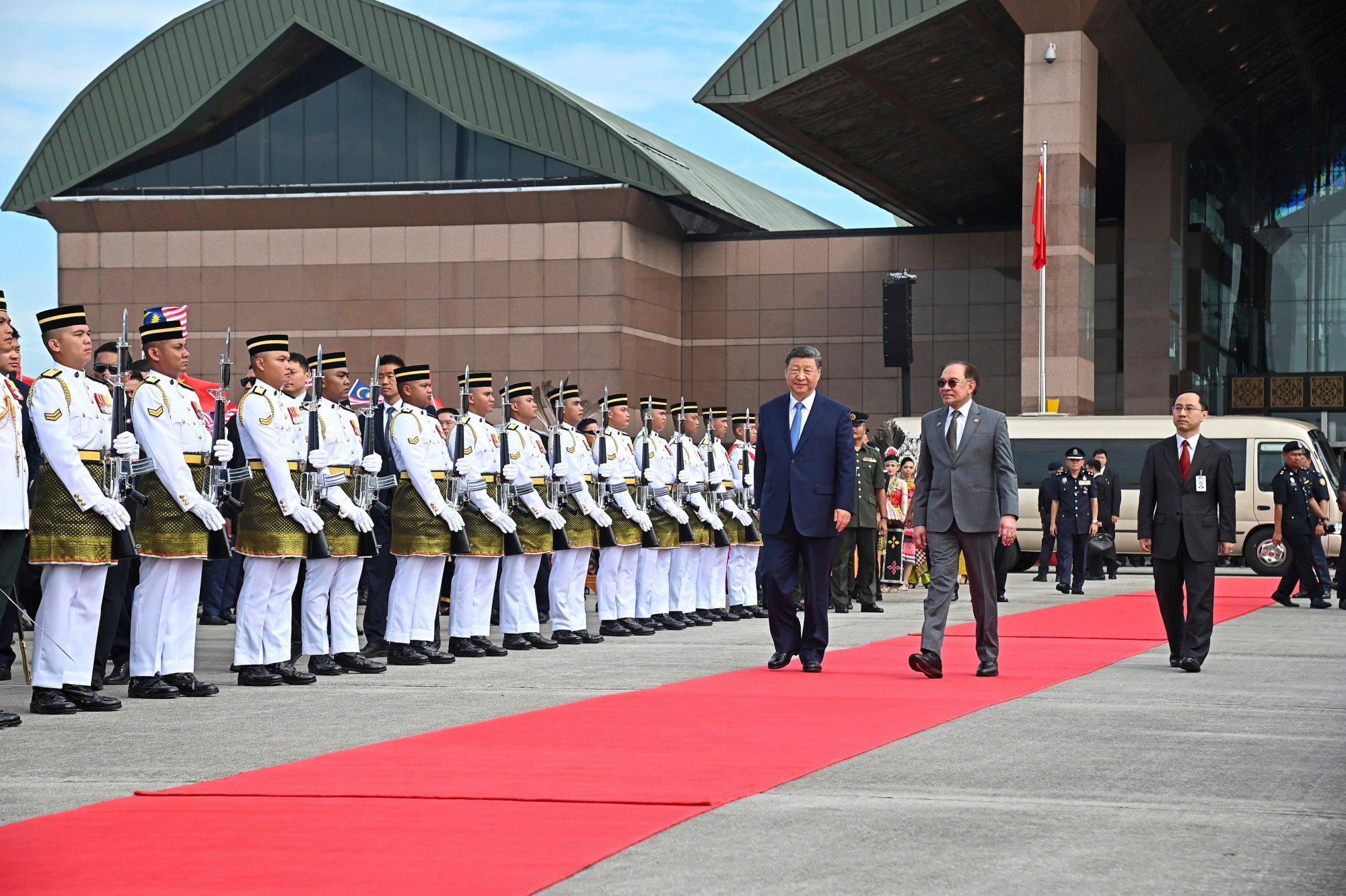

At the same time, Malaysia has been balancing its economic reliance on the US with open criticism of Washington’s complicity in what Mahathir and others have described as a “genocide” in Gaza. Against the backdrop of Trump’s tariffs, Malaysia reaffirmed its commitment to a “shared destiny” with China during a high-profile visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping from April 15 to 17.

Despite this, Mahathir questioned whether current Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim fully grasped the complexities of geopolitics, describing his one-time protégé as “naive” and accusing him of prioritising economic expediency over principle.

Malaysia’s foreign policy has long been defined by neutrality – a legacy established by the country’s second prime minister Tun Abdul Razak, who broke ranks with regional leaders in 1974 to extend a hand to Chairman Mao, establishing formal relations with communist China.

“Malaysia is a neutral country. We want to be friendly with the world. We want to trade with all the countries. We must not side with anyone – neither America nor China,” Mahathir said. “But this government seems to be leaning towards China. At the same time, it is afraid to displease America.”

Anwar has been vocal in his condemnation of Israel’s indiscriminate bombing of Gaza, which has killed more than 52,000 people and left millions starving under a protracted blockade. He expressed his outrage directly to US president Joe Biden at the 2023 Apec Summit, reinforcing his position with a willingness to openly fraternise with the leaders of militant group Hamas’ political wing.

Yet since Trump’s return to power in January, Anwar’s tone appears to have softened – reportedly at the urging of advisers who fear that further criticism of the US could provide a pretext for additional tariffs on Malaysia’s export-dependent economy.

For Mahathir, this cautious approach is unacceptable. Fear, he said, should never justify silence in the face of injustice.

“The government is prepared to tolerate wrong things done by America because it is afraid of America,” he said. “We are all afraid of America. But we have to take a stand on injustice.”